|

martes 16 de noviembre de 2010

THREE PRO-BYZANTINE ARAGONESE INTERVENTIONS

(Article promised to Christiano in Iraklion, Crete, Greece, on October 23th, 2010; the paragraphs about Malta promised to Julia in December 2017)

Last updating Friday, December 21st, 2018

FIRST ARAGONESE INTERVENTION: THE SICILIAN VESPERS (1282)

In 1261, Michael VIII Palaiologos (Παλαιολογος) entered Constantinople, thus ending the Latin Empire, whose rule began in 1204 in Constantinople perpetrating the greatest looting of works of art and relics ever seen in History.

Michael VIII Palaiologos, solemnly crowned in St. Sophia by the Patriarch, proposed himself as prime purpose the communion with Rome. Despite the passionate resistance of the Byzantine clergy, he succeeded in forcing a part of the hierarchy to

accept it. The solemn act of union took place on July 6th, 1274, at the XIVth Ecumenical Council of Lyons II, under Pope Gregory X (1271-1276): The megas logothetes (μεγας

λογοθετης), Giorgios Akropolites, acknowledged under oath, on behalf of the Emperor, the primacy of the Pope, as well as the Roman faith.

Meanwhile, many Sicilians, fleeing Anjou's rule in Sicily, found refuge in the dominions of Peter III the Great, King of Aragon. Count Guido de Montefeltro, the Marquis of Monferrato, and Conrado of Antiochia - grandson of Emperor Frederick

II-, were among the Italians pushing the King of Aragon to intervene in Sicily. The most active and efficient Sicilian refugee was Joan de Proxita, that Peter III the Great created hereditary lord of the castles and towns of Luxen (today

Luchente), Benizano (today Benisanó), and Palma (in Alfauir, La Safor), in the Kingdom of Valencia (1277). It was Joan de Proxita who concorded the Pope Nicholas III with the Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. Twice traveling in secret to

Constantinople, he persuaded the Emperor in 1280 to forward thirty thousand ounces of gold to the King of Aragon to finance the war against Charles of Anjou. The restless Proxita travelled then to Sicily, where he allied himself in secret with

Alaimo de Lentin, Palmerio Abbad and Galterio de Calatagiron, all three outstanding leaders in the island.

But then (1281) died Nicholas III, and was elected Pope the Frenchman Martin IV, who staunchly supported Charles of Anjou, both seeking to rebuild the Latin Empire in Byzantium. Over the newly reconstructed Greek Empire, still fragile, hung thus

a deadly threat, but the high diplomacy designed by the smart Palaiologos, devised a radical solution. In the terrible Sicilian Vespers (March 30th, 1282), all French in Sicily were massacred indiscriminately. It has been said that M.A.F.I.A.

are only the initials of Morte Ai Francesi Italia Anhela (Death to Frenchmen Italy Desires). God knows that better but, in any case, after the massacre there was no turning back, and the world was holding its breath wondering how could Sicilians defend themselves of the expected

retaliation of Anjou. The answer came next August 30th, when 150 ships of the King of Aragon, Peter III the Great arrived in Trapani with a powerful expeditionary force of 15,000 almogávars (1). This force had come to the distressing requests

for help that Sicilian envoys, in black pleading dress, and in black-sailed ships under black flags, presented to Peter III, imploring the intervention of Aragon.

Immediately, in Palermo, the Sicilians swore in most solemnly as his king Peter the Great, which since then entitled himself King of Aragon and Sicily. His ambassadors intimated Charles of Anjou to leave the island on the spot, which he did with great

loss of reputation (end of September 1282). King Peter blitzcrossed Sicily from West to East and, proceeding with his offensive, landed in Calabria with fifteen galleys and 5,000 almogávars. On November 6th, 1282, he seized Catona, in front

of Messina, thus establishing a solid foothold in the Italian peninsula. On the next February 14th, the King of Aragon entered Reggio, abandoned by Anjou. On March 13th, his troops seized and looted Seminara.

Roger de Lauria, appointed Admiral of Aragon

Leaving garrisons in Calabria, the King of Aragon landed back in Messina, where he called to him the noble Roger de Lauria, make him to kneel, and gave him the rod of the Admiralty. Then, recrossing Sicily, now from East to West, reembarked in Trapani on May 11th, heading to Bordeaux to his challenge against Charles of Anjou. After calling at Cagliari (Sardinia), he landed in Cullera, near Valencia, on May 17th. He crossed his

kingdoms of Valencia and Aragon, and from Tarazona he was guided by the Aragonese Domingo Lafiguera in his crossing the Pyrenees and all Gascony, to appear before the Seneschal in Bordeaux of Edward I, King of England. There, the valiant King of Aragon

presented himself on June 1st, the date set for the challenge. Charles of Anjou did not show up [1-a].

Conquest of Malta and Gozo by the Aragonese (1283)

The Admiral set sail from Messina with 21 galleys and, via Capu Passer y Ras Alacran, arrived to Fuente del Xicle near Syracuse, where he watered. The galleys set sail again and, before matines they reached the port of Malta. But the Admiral, instead of attacking by surprise the unprepared fleet of Provence sent by King Charles, ordered to play trumpets and nacres so as to awake the enemies. Thus the galleys of Provence came out and enticed a fierce battle, which lasted till vespers. At this point of the battle, three thousand Provençales had already died. Then, our troops shouted «ˇAragon! ˇAragon! ˇVia sus! ˇVia sus!ť» (Way up! Way up!), got up to the enemy galleys and killed everybody they found on the decks.

Such was the first naval victory of Roger de Lauria as Admiral of Aragon, which resulted in the death of the enemy Admiral, the Marseillais Guillem Cornut, and the capture of all his 22 galleys and one of his two logships, as the other one fled to carry the news of the disaster to Naples and Marseille.

After giving refreshment to his men for two days, the Admiral went up to the city of Malta (Mdina), whose notables offfered to put the city under the guard and protection of the King of Aragon, what was accepted by the Admiral, reciving the oath and hommage from them and from the whole island. The notables gave one thousand ounces of gold in jewels to the Admiral, as well as refreshment and victuals for the galleys, and he left two hundred men as garrison against the castle, that remained under siege. So, the Admiral got satisfied of them, and them of him.

Afterwards they went to the isle of Gozo, and battled the citadel, taking hold of the arrabals (today called Rabat). Afterwards, he attacked the citadel, that surrendered to the Lord King of Aragon on the hands of the Admiral. And he came into it and received the oath and homage of their people, leaving a garrison of one hundred men. Five hundred ounces of gold in jewels were given to him by the notables, as well as refreshment and victuals for the galleys. So, the Admiral got satisfied of them, and them from him.

And the Admiral returned to Sicily, disembarking in Syracuse, where great celebrations were held. [2]

He ordered then to his brother-in-law Conrado Lanza to pass to Malta with 100 knights and 1.000 almogávars to take the castle, and so he did.

Zurita places in [3] firstly the taking of Gozo and afterwards the naval battle, dating it on June 8th, 1283, just followed by the surrender of the city of Malta, that is Mdina. He points out that in the battle Lauria was wounded and Cornut dead when his chest was pierced by a hunting assegai. He reduces to ten the number of galleys captured.

In one way or another, in 1283 both Malta and Gozo were incorporated to the Crown of Aragon, a situation that lasted until the Emperor Charles V, in his condition of King of Sicily, gave them in fief to the Knights of Saint John, together with the city of Tripoli (1530). Two of the conditions imposed were the obligation to send yearly a falcon to the Emperor, or to whatever would be in the future King of Sicily; and that, were the Knights in the future move elsewhere, the full dominion would return then to the King of Sicily.

The interdict

But the Kingdom of Sicily was a fief of the Holy See, which had granted it to Anjou. The reaction of Pope Martin IV, feeling deceived, was devastating. He excommunicated the King of Aragon Peter III the Great, also declaring against him the

terrible injunction: his subjects were thus exempt from their feudal oath of allegiance, and all his realms - not only Sicily - were offered to the first occupant. Not content with this, the Pope condemned as heretic Michael VIII, and in a

statement dated in Orbieto on March 21st 1283, he also excommunicated Andronikos II, who had been co-regent of his father Michael VIII, and sole ruler from the latter's death in 1282. Thus, the ephemeral communion between Greeks and Latins

absolutely wrecked, as Rome itself recanted it.

We find in the Divine Comedy an echo of the impact of these drastic measures, Martin IV being critizied, while Dante wrote about the King of Aragon (Purg, VII, 112 et seq.):

"Quel che par sě membruto e chi s'accorda ... d'ogni valor portó cinta la corda"

(That one so strongly built and that agrees ... of all braveness wore tight the string)

Martin IV did not rest until he saw the invasion of Catalonia by a large and well-equipped French army (Spring of 1285). The invasion, however, ended in a horrible disaster, with death of thousands of horses and soldiers, included the King of

France Philip III the Bold, this one in obscure circumstances.

In any case, since the Sicilian Vespers, the Aragonese liberation of Sicily disabled the island as a springboard against the Greek Empire; in addition, after the terrible catastrophe that became the French invasion of Catalonia, Charles of

Anjou, crushed by the disastrous reality, resigned his claims to the Empire and to Sicily. The Latin "emperor" was no longer taken seriously by anyone, Venice began an approach to the Byzantine Emperor and to the King of Aragon, and the sword of

Damocles that for twenty years had hung over the Byzantine Empire was gone forever.

Pope Martin IV, deeply affected by the disaster, died the same year of 1285 (in March 28th). Also died in this same ominous year the King of France Philip III (as already said), the King of Aragon Peter III (he fall sick at the end of October, and, despite the cares of the famous doctor Arnaldus Villanovensis, so called for being born in Villa Nova de Sancto Martino, today Villanueva de Jiloca, near Daroca (Aragon) [4], that was called to the bedside of the patient, he died in November 11th), and the first of them all, Charles of Anjou (in January 7th) [1].

Three years before (December 11th, 1282), the Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos had preceded them all in their way to the grave, but with the satisfaction of seeing crowned his life's masterwork: the restoration of the Byzantine Empire. "If I ever dare to say - he wrote in his

autobiography - that it was God who ordered their liberty (of the Sicilians) of today, and that this was made through my hands, I would say the truth."

Centuries later, the genial Giuseppe Verdi composed the opera I Vespri Siciliani, inspired in the events just summarized.

---oOo---

SECOND ARAGONESE INTERVENTION (1303-1305): THE ALMOGÁVARS (1)

Origin of the Turkish presence in Anatolia

The ancestors of Turks and Turkomans wandered from the remotest antiquity by the vast spaces of Central Asia. They were to move further and further south, and in the area between the Oxus (Syr Darya) and Jaxartes (Amu Darya), they founded principalities. Later on, already islamized, they infiltrated the Caliphate of Baghdad, where the 26th Caliph al-Qā'im (1031-1075), retaining the spiritual power, handed over the temporal power to the Seljuk Sultan Tughril Beg, which became till his death (1063) Protector of the Caliphate. His successor as Sultan of the Seljuk Turks was his nefew Alp Arslan who, crossing the mountains of Armenia, penetrated with his incursions deep into Anatolia, even sacking Caesarea. At about 1068, all the region was destabilized.

Determined to put an end to that threat, the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes (1068-1071) advanced with a huge but heterogeneous army until Theodosiopolis (today Erzurum), more than one thousand kilometres from Constantinople. He attacked when Alp Arslan and his Sunnites were besieging Alep, which was in the power of the rival Chiite 8th Fatimid Caliph al-Mustansir (1036-1094). The Emperor sent half of his army, commanded by the Frank Roussel de Bailleul and by the Georgian Joseph Tarchanyotes, to cover the area West of lake Van, while he put siege to Mantzikert (today Malazgirt). This fortress, between Theodosiopolis to the North and lake Van to the South, surrendered immediately. But soon arrived the Seljuk leader Alp Arslan with his archers on horse. With a skillful tactic of retreat and reattacking he weakened the heavy cataphracta cavalry of the Byzantines. Roussel and Tarchanyotes escaped westwards to Melitene, while the Byzantine rear, commanded by Andronicos Doucas, also abandonned the battlefield, fleeing northwards. The skillful Alp Arslan thus encircled and defeated crushingly the remaining Byzantines, capturing the Emperor himself (August 19th, 1071), though he fighted as a lion to the end. Romanus IV remained scarcely a week in power of the Sultan Alp Arslan, who treated him with the highest consideration, sharing his table with him as long as the negotiations lasted. In exchange of his freedom, Romanus IV agreed with his adversaries to moderate concessions, given the circumstances. Meanwhile, the real enemies of Romanus IV, wich lurked in the city of the Golden Horn, created Emperor his stepson the young Michael VII Doucas, whose supporters advanced eastwards defeating and encircling Romanus IV in Adana. In exchange of the security of his person, granted under oath, Romanus accepted to surrender dressed as calogero (monk), but he was then treacherously chained, driven to Constantinople, blinded with red hot iron, and secluded in a convent, where he died soon after from his infected wounds (Many more details in my article "La batalla de Manciquerta", in my blog salduie.blogspot.com).

The new government of Michael VII decided not to honour the peace agreement with the Seljuks. Alp Arslan died in 1072, and his successors, feeling deceived, allowed the nomadic Seljuks and Turkomans to spread throughout Central Anatolia, where all Byzantine authority had crumbled down. In nine years, with no army in front, they occupied all the land easily, and already since year 1080 they formed the so-called Sultanate of Rum, centered in the city of Iconium (now Konya).

Status of the Seljuk Turks around 1300

Two centuries after, this state of affairs continued, with a partition of the territory roughly reserving to the Byzantines the coastal regions of the Black Sea, the Ćgean and the Mediterranean, and leaving the inside regions to the Turks. This was the Sultanate of Rum. But the status quo was broken from the moment the Mongols of Hulagu captured Baghdad (1258) and put an end to the Abbasid Caliphate,

killing the last caliph al-Mustacsim. Seljuk Turks from different groups spread farther west, to areas near the Greek coast, looting, killing and kidnapping, in the absence of an effective army that opposed them. So much considered the

Seljuk Turks his conquest what was left of Anatolia, that by lot from among five different hordes, they distributed it as follows:

-To the children of Amurath or Murad, luck got Paflagonia and other lands near the Euxine or Black Sea.

-To Otman, luck conceded Bitinia with the city of Nicomedia (now Izmit), first capital of Constantine.

-To Karaman, luck conceded northern Phrygia.

-To Karkano, southern Phrygia, up to Smyrna.

-To Kalami and his son Karasi, Lydia up to Mysia.

Situation of the Empire around 1300

The international policy of Michael VIII Palaiologos, characterized by the grandeur of its plans, had returned Byzantium to the range of high power. The cornerstone of this policy was the spiritual union with Rome (1274) that, as we have seen,

ended in an absolute fiasco. The Empire was still recovering when Michael VIII died in 1282. He was succeeded by his son Andronikos II (1282-1328), associated to the throne already in his father's life. One of his first acts was to break the

spiritual union with Rome: disappeared the Angevin threat, Constantinople returned to schism. In the socio-economic field, the reconstitution of the Greek Empire meant the victory of the Byzantine aristocracy. The great lay and ecclesiastical landowners were rounding properties and gaining ever wider tax liens. But - and this was much more serious - the ruthless tax burden of the Empire meant that many Christians prefered to

survive under Seljuk rule that to be crushed by heavy taxes, while not being defended militarily by Byzantium. Indeed, the Koran limits taxes strictly, while the Byzantine treasury was never satiated, and that to maintain a court as lavish as ineffective.

In the military field, once abandoned the system of themes, impossible to reinstate after the loss of most of Anatolia to the Turks, the only possible basis of the army were the mercenaries, the money to pay them being obtained from Genoa (Venice

was discredited after its disastrous intervention in the creation of the Latin Empire of Constantinople) in the form of advances, in exchange for exorbitant trade concessions, specified in the treaty of Nymphaeum (1261).

The almogávars, hired by the Empire

To meet the aggressive Turkish incursions, Andronikos II, lacking troops of his own, hired Massagatae mercenaries (called "Alani"), from the lands south of the Danube. But they failed miserably against the Turks. To ask for another Crusade,

after the disastrous precedents, and after the break with Rome, was out of question. What to do? The emperor saw the heaven open when he received the offer to enter to his service as mercenaries, of the companies who had fought in Sicily and

Calabria against the Angevin supported by the Pope, but were no longer needed after the peace of Calatabellota. Its leader, Roger de Flor, as rebounded Friar Templar, although non grato to Rome, or perhaps because of that, inspired full

confidence in Constantinople. Orphan of a German falconer named Blöm, he had frequented the East, where he was estimated, and he spoke excellent Greek. Besides, his best troops came from Aragon, whose blietzkrieg intervention in Sicily had

been hatched and financed by Michael VIII Palaiologos. It seemed the perfect solution.

Aboard 16 galleys and as many carriers, provided by the King of Sicily, that thus got rid of so uncomfortable guests, sixty five hundred almogávars arrived in Constantinople in January 1303, led by Roger de Flor. Roger was created Megaduke,

marrying Mary, niece of the Emperor. The Aragonese Fernando de Ahones was appointed Admiral. Later on (Spring of 1304) would join them another 1200 men with Berenguer de Rocafort, and other 1300 more (Fall of 1304) with the Aragonese nobleman

Don Berenguer de Entenza.

The campaign of 1303

Most of 1303 was spent on weddings, adjustments and preparations. The Emperor authorized the almogávars to fight under their own flags, which were the four-barred seńal of the Kingdom of Aragon and the gonfalon of the Kingdom of Sicily.

Soon there was an almost generalized fight between almogávars and Genoese in Constantinople. The Emperor, despite the lateness of the season, persuaded the Megaduke to pass to Asia with his almogávars, accompanied by

Marulli and his Byzantine troops, and George and his "Alani" mercenaries. They landed in the small peninsula of Artaki, on the eastern shore of the Marmara Sea, where once stood Cyzicus. The peninsula was defended by a wall or repair. Just

arrived, they went out at midnight and at early morning they were attacking by surprise the camp of Karaman Turks, located just seven miles away, where the warriors slept with their families. The enemy suffered an appalling massacre at this

first encounter, leaving in the field three thousand horses and ten thousand infantry dead; the rest fled. The Megaduke had ordered every male over ten years to be exterminated, and so was done. Women and children were enslaved.

The enthusiasm was enormous in the city of Constantine, and like wildfire word spread that "the hordes of Sesa and Tin had been disrupted by the Franks."

"Entrance of Roger de Flor in Constantinople",

oil on canvas by José Moreno Carbonero (*Málaga, 1858-Madrid, 1945).

This picture hangs in the Salon des pas perdus of the Senate of Spain, in Madrid.

It shows the triunfal entrance after their first victory in Artaki.

With the arrival of November and the snow, the army withdrew to its winter quarters at Cape Artaki.

The first campaign of 1304

The Emperor, confident in the effectivity of his new almogávar army, set it as target for 1304 to lift the siege that the Karaman Turks had put over the city of Philadelphia (now Alașehir). Philadelphia, on the banks of the Pactolus, is one of the Seven Churches of Asia mentioned in the book of Apocalipsis. In early April there was a very serious affray between almogavars and "Alani", in which more than three hundred "Alani" were killed,

including the son of George, his boss. Of the others, few wanted to follow Roger, who only retained a few thousand.

Finally, in early May 1304, the Megaduke set out, with Marulli and his Byzantines. The troops headed from Anchirao towards Germe, besieged by the Turks, who retired in view of what was about to fall over them. Then they went to another village,

its name unknown, but in which almogávars were about to hang a dignitary, were it not prevented by Marulli. The army proceeded to Geliana, and although several distress calls were received from other cities, the Megaduke Roger chosed to go

directly to Philadelphia, the main objective set by the Emperor.

The Battle of Philadelphia

Two miles from the city both forces got sight of each other, the Turks ready to face the enemy. Although they ranked eight thousand horses and twelve thousand infantry men, they were almost wiped out in a great battle, escaping with their lives only 1,500 Turks.

The citizens of Philadelphia, headed by Bishop Teolepto, came out to welcome their deliverers. The Megaduke Roger spent fifteen days in the city. He then fred Culla (current Kula), northeast of Philadelphia, proceeding to Nice (Nisa in Lycia, not to be mistaken with Nyssa in Cappadocia, the homeland of St. Gregory of Nyssa), and from there to Magnesia, a walled city at the foot of Mount Sipylus (in the meridian 27ş 20' East of Greenwich ), where the booty of the

almogávars was left for safekeeping. Alongside this Magnesia, the year 190 BC, Scipio Asiaticus (with the advise of his brother Scipio Africanus) had beaten Antiochus III the Great, forcing his withdrawal beyond Taurus Mountains.

The battle of Tira

A distressing call for help reached at this time the expedition from the city of Tira, or Tyrra (now Tire), east of Ephesus, by the river Meander. There they came, walking thirty-seven miles in seventeen hours, and entered the

city without being seen by the enemy.

When the Turks approached with insolent spirit, a departure from the almogávars resulted in a big and bloody victory, with the killing of many attackers. However, the Seneschal of the army, Corbalán de Alet, was killed in combat. He was buried in a

marble tomb in a chapel next, where it was said Saint George was buried.

Finally, Roger de Flor established its base in Ephesus (2), then called Altobosco, in front of his own fleet anchored in the island of Chios.

The second campaign of 1304

The second military objective set by the Emperor to the almogávars this year of 1304 was even bolder by its remoteness. Chased the enemy of the Ćgean coast, the objective was now to penetrate much farther east.

The fleet, as said ut supra, was anchored in the island of Chios under the command of Admiral Fernando de Ahones. By direct order of the Emperor, the newcomer strengthening of Berenguer de Rocafort, with two hundred horsemen and one thousand

almogávars more, boarded the ships at the very last moment.

The fortified city of Ania and its successive names

Geronimo Çurita (nowadays written Jerónimo Zurita), in his magnum opus "Anales de la Corona de Aragón" (Annals of the Crown of Aragon), cites the city of Dania, the name probably deriving from the script d'Ania, mistakenly placing it in the Ćgean region. Don Francisco de Moncada also steps over the same error in [6]. This Ania is none other than the current Alanya, in the east coast of Pamphylia, and on the borders with Cilicia (dominion then of the Christian kingdom of Little Armenia), located at the point where meridian 32° East of Greenwich intersects the southern coast of Anatolia.

Ania occupies a peninsula with an analogy to Peńíscola, but much larger. Today we can see, not just a

castle, but rather an imposing defensive complex formed by a wall of 6.5 km in circumference, equipped with 400 cisterns, and flanked by 140 towers. The most imposing of them all is the Red Tower, enormous octagonal prism of 33 m that remembers the Torre del Oro of Seville, and that, by the sea, controls the Eastern border of the complex.

In the year 190 BC, King Antiochus III Megas (The Great) entrusted Hannibal - at the time refugiated under his protection - the mission of building up a fleet in Tyre and bringing it back to the Ćgean Sea to reinforce the one of his admiral Polixenidas. Hannibal navigated westwards with these just hired fleet when, at the large of Side, appeared against him a fleet of Rhodes, enemy of King Antiochus, strong of 36 ships. The fleet of Hannibal was more numerous, and the veteran Carthaginian -he must already be almost 60- commanded the port wing, that is, the side of open sea. The starboard wing was under the command of Apollonius, Seleucid dignitary. Eudamus, the Rodian admiral, much more expert in the sea, was able to turn over the initial advantage of Hannibal, that at the end of the day and after suffering heavy losses, was forced to turn around and seek refuge in Ania, then called Korakesion. (Titus Livius, XXXVII, 23, 2).

Later on, the usurper Tryphon constructed a fortress in Korakesion, completed by Antiochus VII Euergetes Sidetes.

Korakesion reappears -written in Latin Coracesium- when in the year 67 BC, Pompeius defeats in its waters the pirates that then infested these part of the Mediterranean.

Much later, in the VIth and VIIth centuries, Byzantium would reinforce considerably the defences, face to the Arab attacks, receiving then the name of Kalon Oros, the Beautiful Mountain.

Since the ominous IVth Crusade, the rock and the fortress would be ruled by the Christian kingdom of Little Armenia. But soon the Seljuk Sultan cAlā' ad-Dīn Keykubat would conquer these lands in 1221 to the Armenian Kyr Vart. Keykubat married the daughter of the Armenian King and, through the eminent builder of Aleppo Abū cAlī al-Kattāni, he would construct between 1226 and 1232 most of the impressive fortified precinct that we admire nowadays, included the Red Tower (in Turkish, Kizil Kule), key at its turn of the magnificent shipyards. Converted in summer residence and into an important export and import center, the Seljuk rulers named it cAlāyā, but the Italian merchants called it Candelore. When the Seljuk domains were divided in about 1300, Ania fall to the horde of Karaman.

Modern Turkey has turned out this enclave and its splendid beaches into a prosperous tourist summer center, as well for Turk nationals as for foreigners. On the other hand, the Turkish authorities, besides keeping impecably all the historical site, go on performing archaelogical investigations (2005), having discovered a small Byzantine church.

The ancient diocese of Dania in partibus infidelium would then be identified with Ania.

We also have some news about how was Ania in the XIVth century, as the Tangier-born never resting traveler Ibn Battūta visited it some years later, when already islamized, writing its name cAlāyā, and noting "where begins Anatolia." (He entered from Latakia on the Syrian coast). Ibn Battūta writes: "... this coastal city of cAlāyā is large and inhabited by Turkomans ... on top of the town there is a magnificent and impregnable castle, built by the exalted Sultan cAlā' ad-Dīn ar-Rūmī

... the king of cAlāyā, Yūsuf Beg ben Qaramān, lives within ten miles of the city ..." [7]

Present spelling Alanya is attributed to Atatürk himself, founder of the modern Turkish Republic, when he decided that the Turkish language, abandonning the alifate, would be written with the Latin alphabet.

The almogávar adventure goes on

In any case, it seems that such a formidable fortress was held by Andronikos II that year of 1304, as the texts does not say that Admiral Fernando de Ahones

took it, but that the fleet of the almogávars anchored under the protection of Ania's fortifications. The Megaduke sent Ramón Muntaner to Ania to request

the presence of Rocafort, who he had not yet seen in person. Given the dangerous trip to Ephesus, Rocafort was accompanied by all his people, but 500 almogávars left in Ania with the fleet. This move contradicted the explicit orders of the

Emperor, who had sent Rocafort directly to Ania. It was probably intended to establish bonds of comradeship among veterans and new recruits, reinforcing the interlock of all. Be that as it may, the Megaduke gave to

Rocafort at Ephesus the same range of steward of the army that had held the deceased Corbalán de Alet, and the whole army with its brand-new Seneschal began moving towards Ania, which is more than 400 km east of Ephesus.

First clash in the orchards of Ania

Just arrived to Ania our almogávars, the Karaman leader Sarcano dared to run the orchards, which excited the almogávars out against the enemy, without even waiting for orders of the captains. The Turkomans were firmly

rejected, leaving one thousand horses and two thousand footmen dead in the battlefield.

Second and colossal battle

After a break of more than two weeks in Ania, Roger and the other captains in charge, advanced with the whole army in good order, its flags erect, from Ania and along the coast eastwards, toward the kingdom of Little

Armenia (that, as already mentioned, then occupied Cilicia). The army reached the Iron Gate, the point that from the coast goes up through the Taurus Mountains, the way to the stronghold of Karaman. There is the modern Demirtaș (Turkish

demir = iron; taș = rock). Recognizing the field, they discovered the Turkoman army, hidden in the valleys.

It was August 15th, festivity of the Virgin of August, of the year ot Our Lord of 1304.

In this decisive showdown, Karaman lined ten thousand horses and twenty thousand footmen. Our men not even reached nine thousand, between horses and almogávars. These, hitting the rock till making sparks with the ferrule of their spears, uttered their terrible war cry Desperta, ferro! and rushed against the enemy. The battle was of a violence and ferocity never seen before. When the valiant Turkomans appeared on the verge of victory, our men shouted Aragon, Aragon!, as written by the Catalan Ramón Muntaner in [2], and in a new supreme push, drove away the enemy.

On its reach, only the arrival of night ended the indiscriminate killing. Next morning, a silence of death hovered over those rugged mountains. In all parts layed scattered lots of dead, men as well as horses, Muntaner figuring out the first up to twelve thousand, and six thousand of the latter.

Then they advanced along the gorge of the Iron Gate, where they waited the enemy for three days, with no living soul daring to show up.

Back to Ania

Roger did not consider prudent to further advance into that terra incognita, and determined to return to Ania, having already defeated the enemy, along that year of 1304, no fewer than in four pitched battles.

The Emperor orders the army to return to Europe

In their way back to Ania, the army received an Emperor's peremptory order to leave everything and go back to Europe to suppress an uprising.

The order caused shock and consternation, because the enemy was badly broken, but far from destroyed, and a retreat in this situation could frustrate - as it eventually did - the exploitation of success. The Megaduke, always wise, once again

persuaded his warriors to obey, and they marched westwards towards the Ćgean in short journeys, so as not giving a sense of withdrawal, and along the coast, in parallel with the fleet. Thus was their approach to Ephesus, in the hope of returning the following

spring, already in 1305, to consolidate the successes achieved so far.

But fate would order events very differently.

They learned then that Ataliote, the captain of Magnesia, raised in arms, had slaughtered the almogávar garrison, seizing the booty stored there. The Megaduke besieged Magnesia, to retrieve the fruit of so many victories. But the almogávars

lacked poliorcetic means, and the siege prolonged itself. Then the Emperor's insistence in his calls redoubled, urging them to immediately cross to Europe, and to camp at Gallipoli, in the Thracian Chersonese. So they did.

Their mere presence in Europe enabled the Emperor to negotiate successfully the revolt's end. However, suspicion arose that the presumed uprising had been only a pretext for dark purposes. God knows better all this. The problem solved,

the Emperor told our men to spend the winter in Gallipoli.

With these most outstanding feats, the almogávars had not less than fred Greek Anatolia from Karaman Turks, not only defeated but harshly broken. There was standing up, however, the Sultanate of Rum.

In comes Don Berenguer de Entenza. The Megaduke is created Cćsar of the Empire

Then came to Gallipoli a powerful character in the Kingdom of Aragon, Don Berenguer de Entenza, with another 300 horses and one thousand almogávars more. Don Berenguer was hesitant to go to Constantinople, until the insistence of the Emperor

persuaded him to do so. In full hearing before the august person of the Basileus, Roger de Flor, recognizing the noble lineage of Entenza, declared himself under his orders, bareheaded himself from the hat of Megaduke, and placed it over the head of

Entenza.

Entenza

Solemnly, however, the Emperor, confirming in the dignity of Megaduke Don Berenguer, created Roger de Flor Cćsar of the Empire.

Infeudation of the "Kingdom of Anatolia"

Andronikos II decided to pay the army with a newly minted coin that he named basilios, but that was of very low grade. The almogávars, that had lost their booty in Magnesia, were forced to pay their accommodation and other expenses in that devalued currency, despised by the population. Frictions arose with the Greeks, while our men felt cheated by this Byzantine move.

And if the overwhelming victories of the almogávars began to worry the Byzantines, still more were they concerned that these shock troops could be only the spearhead of a full-scale landing of Aragonese troops, to implant a new Latin Empire.

Winter was spent between recriminations and negotiations. The imperial Treasury was exhaust, leaving only the resource of new levies. The Emperor preferred that the Cćsar himself assumed the thankless task, giving him the

"Kingdom of Anatolia" in fee. Thus, taking over the responsibility of paying the troops, he would free the imperial Treasury of such unbearable burden.

Concerns and suspicions

A bad thing was that the power accumulated in the Cćsar Roger was already comparable to that of the Emperor.

The trouble was that his victories had revealed the failure not only of the "Alani" mercenaries and the Genoese allies, but even of the Byzantine forces themselves and, worse still, their commander, co-emperor Michael. He feared that the

Cćsar, as feudal lord of the Kingdom of Anatolia, with his self army and navy, could escape imperial control, as the Kingdom of Anatolia covered a wider territory than the rest of Byzantium. Probably, their fears would be shared by many Greeks, high and low. In addition, the Empire had no troops to oppose the so far undefeated almogávars, if need arised.

All this evidences, all of these jealousies and suspicions, found their hub in the person of Michael IX, son, heir and co-emperor of Andronikos II.

The Byzantine perfidy

Once entered the year 1305, on arrival of Spring, the army was ready to return to Asia, namely to his Kingdom of Anatolia. This Kingdom, as we say, was officially granted in fief to the Cćsar Roger de Flor, with power to levy taxes and administer justice: with simple and mixed empire. The Cćsar considered it essential, before entering the campaign, to pay a courtesy visit to co-emperor Michael IX, who held his court at Adrianople. He was seeking to dispel fears and suspicions propagated by hidden adversaries of his warriors, adversaries that as we will see proved far more dangerous than the very Turkish enemies.

Some imperial counselors were suspecting that the almogávars might eventually end up conquering the Kingdom of Anatolia for themselves and not for the Empire.

Michael IX took precautions and surrounded himself by his faithful "Alani", while excogitating means to end with the almogávar threat, obvious to him. How to ward off the danger? No doubt Andronikos II and his entourage were people of high

cultural level. And as the bloody Sicilian version of the Vespers of Ephesus (3) had reached an outstanding success, they perhaps thank that another classical precedent, as outlined in the Anabasis [7] and also stained with blood, would take effect.

The tactic chosen was patent on April 4th, 1305, when Roger de Flor and the other captains were killed by the "Alani" mercenaries in the very palace of Michael IX, following a feast to which he had invited them. Imperial advisers may have

believed that, by applying to Roger and the other almogávar captains the same kind of betrayal that Tissaphernes, the Machiavellian satrap of Artaxerxes, had perpetrated against Clearchus and the other generals of the Ten Thousand, they would

get better results than the said satrap, defined by Xenophon as "the most wicked of men."

They prooved tragically wrong.

Breaking off the oath of allegiance

Two envoys of the Megaduke Don Berenguer de Entenza went from Gallipoli to Constantinople to the Emperor to inquire from his lips the truth of the facts. They were received in audience by the Basileus, who gave them as all explanation that he had not ordered the killing. Known that response totally unsatisfactory, two new messengers were sent from Gallipoli to Constantinople to announce officially and solemnly to Andronikos II that the almogávar army, given the enormity of the treacherous crime, considered broken, according to feudal custom, their oath of allegiance to the Emperor.

Heinous crime and attempted extermination

But when the messengers, on their return, crossed Redristo, they were attacked, killed, dismembered, and their pieces hanged from butchers' hooks.

Soon then, Don Berenguer de Entenza was arrested, also treacherously, by a Genoese ship.

Little after, news came that the co-emperor Michael IX advanced against the almogávars with seventeen thousand horsemen and one hundred thousand footmen. The Aragonese, in a new "anabasis", did not wait at Gallipoli, but "rose" to

meet the co-emperor, settling a fierce and unequal battle, which lasted until nightfall. Only then the Byzantines were defeated, being Michael IX wounded in the face by a sailor named Bernardo Ferrer.

The "Catalan" Revenge

Already in open war against the Empire, the almogávars entered Redristo at dawn, "and upon all persons found - says Ramón Muntaner in [5] - men, women and children, they did what the messengers were done, that for nobody in the world they wanted to renounce. And it is true that it was a great cruelty, but that revenge they took. "

Knowing then that the nine thousand "Alani" mercenaries executors of the treacherous crime of April 4 were returning home, carrying gold, and had already crossed the northern borders of the Empire, the almogávars ran and catched them. In the words of journalist and writer Arturo Pérez Reverte in [8], "made hash out of eighty five hundred of them, and took over their gold and their women." Then, they came back. There was no enemy left.

Disastrous consequences for the Empire

Ramón Muntaner, an eyewitness who was part of the expeditionary force, writes in [5]:

"The Turks whom we had driven from Anatolia, knowing the death of the Cćsar and the imprisonment of Don Berenguer de Entenza, ... came back to Anatolia and submitted again all cities and towns and castles of the Byzantines, more closely than they were before ... All the Kingdom of Anatolia was lost, as the Turks occupied it ... and all of Romania was devastated by us, because there was no town or city not sacked and burned by us." (Romania appointed at this time the European territories of the Empire).

The Turks, allied to the almogávars

The almogávars received in Gallipoli offers of alliance from the Turks, that were accepted, and twelve hundred of them, with their leader Xemelic, came to Europe under vassalage of the almogávars. For two years, the almogávars and their Turkish allies mercilessly ravaged the fields of Thrace, ushering to History the terrible "Catalan" Revenge. The almogávars found in the Muslim Turks who joined them a fierce loyalty, in tragical contrast with the criminal betrayal

suffered from the Byzantine Christians, to whom they had just fred from their enemies, with bloodshed and triumphant glory.

This allowed the Turks to learn about the weapons and tactics of the almogávars, and recognize the European territory that they would eventually submit a century and a half later, and up to this day.

They cross to Attica and Bśotia

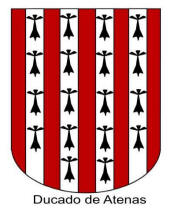

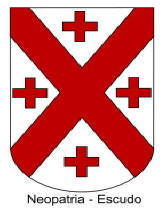

After complicated adventures, the almogávars moved to Greece, and in Attica and Bśotia they ended up beating Jean de la Brenne, Latin Duke of Athens, who was beheaded after the extermination of his army. Thus they took over the Duchy of Athens, and later on over the Duchy of Neopatria (Thebes and all Bśotia). Years later, in 1380, already in the times of Peter IV the Ceremonious, this King of Aragon accepted to include both Duchies among his domains.

---oOo---

THIRD ARAGONESE INTERVENTION: THE NAVAL BATTLE OF CONSTANTINOPLE (1352)

Andronikos II associated to the Empire, after the untimely death of his son Michael IX (Thessaloniki, 1320), his grandson Andronikos III, young man of great physical beauty and remarkable political skills. He was also appointed successor to the Empire.

There were periods of great stress and even, for three times, of civil war between grandfather and grandson. As he began his reign, which would last from 1328 to 1341, Andronikos III appointed great domestikos (μεγας δομεστικος)

John Kantakouzenos, young tycoon with great gifts of statesmanship, which became his right arm. His qualities stood him always above everybody, even over the Emperor himself.

In 1341, at the death of Andronikos III, his son and successor, John V, was 9 years old, and the Kantakouzenos assumed the regency. Thus he spoke at a council of war:

"If it happens, with the help of God, that the Latins of the Peloponnese submit themselves to the Empire, the Catalans of Attica and Bśotia will have no alternative but to join us, by choice or against their will. Then, the power of the Romans

will spread, as in the past, from the Peloponnese to Byzantium, and is therefore likely that Serbs and other Barbarian neighbors give reparations for all the outrages that they have perpetrated for so long time."

Reality had nothing to do with these dreams of grandeur: a new civil war broke out in Byzantium between the regent John IV Kantakouzenos and the self-styled defenders of child John V.

To make matters worse, in 1348 fell over Constantinople the deadly scourge of the Black Death, which struck the capital and ended up infecting the whole Europe. The plague and the civil war depleted the remaining energies of Byzantium.

During the civil war the Serbs took from Byzantium more than half the country still remaining to it. The Empire was reduced to Thrace, the islands of northern Ćgean, Thessaloniki, isolated between the Serbian conquests, and imperial possessions in

the far away Peloponnese.

The country, that to the the horrors of the civil war, the sacks of the Turkish bands and the Serbian invasion, had added the terrible ravages of the Black Death, looked like a desert. Empress Anna pledged to Venice the jewels of the imperial

crown against a loan of 30,000 gold ducats.

Emperor John IV Kantakouzenos decided to cut trade privileges to the Genoese, whose prosperity contrasted with the squalid imperial finances. He then lowered imperial sea tariffs, in order to attract trade to the port of Constantinople. Genoa, its interests seriously damaged, sent its ships against Byzantium, destroying the imperial fleet in 1349. Furthermore, in 1350, the Genoese, who had imposed their commercial monopoly on the entire Black Sea, confiscated in Caffa (Crimea) the goods of several Venetian

ships that pretended to ignore the blockade, this action worthing tantamount to a declaration of war.

In comes Peter IV, King of Aragon (1335-1387)

Peter IV the Ceremonious, King of Aragon, had just taken over the kingdom of Majorca and the counties of Roussillon and Cerdagne. After the bankruptcy of Florence in 1345, he was since 1346 striking gold florins in his mint of

Perpignan, and turning Aragon into a great naval and economic power.

Triple Alliance between Venice, the Empire, and Aragon

Andrea Dandolo, at the time Dux of Venice (1343-1354), sent ambassadors to Perpignan proposing to Peter IV a combined naval intervention in Constantinople. The Ceremonious accepted, and the Kingdom of Aragon and the Serenissima Republic of Venice - duo prepotenti popoli (two prepotent peoples), as historians said at the time - readied their Armadas to fight Genoa, and in support of Emperor Kantakouzenos.

Catalogue of the ships

The King of Aragon received from Venice a certain amount of money for each armed galley, appointing Ponce de Santa Pau his Admiral, and arming and rigging in a short time 24 galleys in Barcelona, Valencia, Mallorca and Colibre (Roussillon).

The ships of the Kingdom of Valencia and of Colibre were under the command of Vice Admiral Bernard Ripol, who sailed directly to Constantinople.

The ships of the Kingdom of Mallorca were commanded by Vice Admiral Rodrigo de San Martín.

The ships of the marinas of Gerona and Tarragona, that went to Barcelona, were under the command of Vice Admiral Bonanat Dezcoll.

The navigation to the theatre of operations

Admiral Santa Pau set sail with the 21 galleys of Majorca and Barcelona in July of 1351. He took towards Mahon (Minorca), and from there to Caller (now Cagliari, Sardinia), where he stayed three days. He then proceeded to Sicily, in whose waters he found the Venetian fleet, strong of 20 galleys, commanded by messer Pancracio Giustiniani. The two allied Armadas departed from Messina, mixed their ships, and brought together toward Cape

Leuca, later on called Cape Santa Maura, on the coast of Epirus.

In the navigation between this cape and Romania the ships were separated by a storm, concentrating afterwards in the then Venetian port of Coron (modern Koroni, Messenia, Greece), where they stated the loss of one Catalan galley.

Genoese ships lead by Perin de Grimaldo were then attacking the Venetian possession of Negroponte (now Calcis), but when news came that a powerful combined fleet of Aragon and Venice was nearby, they left as fast as they could seeking refuge in his base of Pera.

Then, the allied ships arrived to Negroponte, from where they reached and crossed the Dardanelles towards Constantinople.

Already inside the Marmara Sea, they met Nicholas Pisano, captain general of the Common of Venice, with 14 galleys, and were also reached by the above mentioned Vice Admiral of Valencia, with 4 galleys.

And with tough time, they all took shelter in an uninhabited island ten miles from Constantinople.

The Naval Battle of Constantinople (1352): a Pyrrhic victory

When it cleared up, the 59 galleys of the combined fleet sailed, their banners raised, towards Constantinople, where they saw the incoming 9 galleys put together by the Emperor Kantakouzenos.

The imposing Genoese fleet, strong of 65 galleys and led by Perin de Grimaldo, which from Pera, across the Golden Horn, saw everything, sailed also with raised banners, trying to prevent the merger of the meager imperial armada

with its Western allies. But in that very moment, "moved so angry and furious storm -Zurita writes in [5]- that the Genoese suddenly turned around and went back the way of Pera, and in front of that place they anchored, divided

in groups of 4 and 5, and 7 or more, and thus spread all before Pera for about a mile, for fear of the storm."

And the allies began attacking these groups at the hour of compline. Thus locked up the great naval battle between the two armadas, in front of the Bosphorus, in waters of Constantinople.

It was February 13th, 1352.

The strong storm spread a lot of confusion among the ships, but even so the battle continued into the night ("till time of the first chickens", writes Peter IV in his Crónica), "fighting all with such nerve and determination, that

many ships were destroyed and dismantled. And finally the Genoese were totally disbanded and overcome" -writes Zurita; and he adds:- "Over the galleys of the Genoese that struck land because of the storm, we won three and

twenty galleys". But the Serenissima lost 14 galleys, and Aragon another 14, although part of the crews saved themselves in Constantinople. Moreover, the Allies lost his two Admirals: messer Giustiniani died in a few days, and

Santa Pau, wounded in combat, also died in Constantinople in the month of March. Also fell in battle Ripol, Vice Admiral of Valencia, and more than 3,000 men between subjects of the King of Aragon and of the Serenissima.

Out of the galleys that sailed from Aragon, only ten returned, as the eleventh, when repatriating the body of Santa Pau, was sunk by a flotilla of ten Genoese ships being sent to Romania to replace losses.

Epilogue

Aragon left Eastern Mediterranean, concentrating its power in Sardinia, which he finally won after defeating the Genoese. For his part, emperor Kantakouzenos, left even more alone and helpless than before, had to

capitulate witn Genoa and renew the trade concessions that were bleeding the Empire.

The Turks install themselves permanently in Europe

The same year (1352) of the great naval battle of Constantinople between Christians, the Turks decided to end the era of no target cavalcades, settling permanently in the stronghold of Tzympe, on the European shore, near Gallipoli.

The Byzantine reaction was suicidal: a new civil war broke out, long and hard, to be eventually won by the Kantakouzenos: in 1354, in the church of Blacherna, his son Matthew received from the hands of the Emperor and the new Patriarch ad hoc

the crown of co-emperor and the rank of heir to his father.

Little lasted the triumph of the Kantakouzenos. The Turks seized the same year (1354) Gallipoli itself, strengthening their foothold in Europe to make it impregnable. The alarm in Constantinople was great, and great the discredit of the Emperor.

John V having come of age (1354), the Kantakouzenos had to abdicate; he retired to a convent, where he still lived 30 years, writing his famous history.

END

---oOo---

NOTES OF THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION

(1) The Spanish word "almogávar" derives from the Arabic المغاور

(al-mugāwir), the expeditionary. The almogávars were very tough infantry troops, active in the southern frontiers of the Kingdom of Aragon with Saracen territory. They came as volunteers a bit from everywhere, even from Sicily and Calabria, and we could say that their fierce spirit revived the mentality of the ancient Celtiberians.

(2) Ephesus, Greek-speaking city, was for centuries the main one in the southwest quadrant of Asia Minor.

In the area, the ancient cult to goddess Cybele was substituted, under Jonic influence, by the cult to Artemissa. The splendid temple of this goddess, the Artemission, became one of the Seven Marvels of the Hellenistic world, but nothing is

left of it today. Over the centuries, the city suffered tremendous damages by several earthquakes; as well, the Meander River was gradually silting in its port, and creating, moreover, by the city, a malaria-infested marshland.

Altobosco probably refers to a hill overlooking the modern town of Seljuk, that keeps the ruins of a church built over the traditional burial place of Saint John the Evangelist, who is said to have written part of his Gospel in Ephesus. In

another nearby forest, overlooking the sea, archaeologists have recently rediscovered and rebuilt the house of the Virgin Mary, visited by Popes Paul VI, John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Not far away, obviously in the sea, lies the island of

Patmos, also linked to Saint John.

(3) In the so-called Vespers of Ephesus, the year 88 BC, some 80,000 Romans were killed in that city and others of Asia Minor, at the instigation of Mithridates VI Eupator, king of Pontus. Thus began the first of four wars between the Roman

Republic and Mithridates.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] For the Sicilian Vespers -that are not so called in the text- see Anales de la Corona de Aragón, Book IV, specially § XIII De la confederación y liga que Joan de Proxita concordó entre el papa Nicolao III y el

emperador Miguel Paleólogo y el rey de Aragón, contra Carlos rey de Sicilia. Y de la armada que mandó el rey juntar para pasar a Constantina (About the confederation and league that John de Proxita concorded between Pope Nicholas III and

Emperor Michael Palaiologos and the King of Aragon, against Charles King of Sicily. And about the Armada that the King ordered to assemble to cross to Constantine); and § XVII De la rebelión de los sicilianos contra el rey Carlos, y cómo fueron echados los franceses de la isla (About the rebellion of Sicilians against King Charles, and how were the Frenchmen expelled from the island), and § ss. Author: Geronimo Zurita, Cronista del Reino de Aragón; edition prepared by Ángel Canellas López, Institución Fernando el Católico; Zaragoza, 1970.

[2] Crónica, by Ramón Muntaner; Spanish translation by J. F. Vidal Jové; editor: Alianza Editorial; Madrid, 1970.

[3] Anales de la Corona de Aragón, Book IV; § XLIII De la batalla que el almirante Roger de Lauria venció a los franceses en Malta, p. 160

(About the battle in which the Admiral Roger de Lauria overcame the French in Malta). Author: Geronimo Zurita, Cronista del Reino de Aragón; edition prepared by Ángel Canellas López, Institución Fernando el Católico; Zaragoza, 1970.

[4] Arnaldo de Villanova (polyptic), Institución Fernando el Católico, public. nş 2.160; author: Ricardo Centellas; Zaragoza, 2001.

[5] Anales de la Corona de Aragón, Book VIII; § XLVI De la armada que el rey envió con Ponce de Santa Pau en ayuda de Venecia; y de la

batalla que tuvieron con la armada genovesa delante de Constantinopla. (About the Armada that the King sent with Ponce de Santa Pau in aid of Venice; and about the battle they had with the Genoese fleet before Constantinople). Author: Geronimo Zurita, Cronista del Reino de Aragón; edition prepared by Ángel Canellas López, Institución Fernando el Católico; Zaragoza, 1973.

[6] Crónica de Pedro IV, written under the auspices of the King Peter IV of Aragon; editor Amédée Pagés, Toulouse-Paris, 1942.

[7] La expedición de los Diez Mil (Anábasis), by Xenophon; Spanish translation, published by Espasa-Calpe, Colección Austral, sixth edition; Madrid, 1958.

[8] Historia del Estado Bizantino, by G. Ostrogorsky; Editor: Akal/Universitaria; Madrid, 1983; Spanish translation of the German original Die Geschichte des bizantinischen Staaten, Munich, 1963.

[9] Expedición de los catalanes y aragoneses contra turcos y griegos; by don Francisco de Moncada; edita Espasa-Calpe Argentina, Colección Austral, segunda edición; Buenos Aires, 1948.

[10] A través del Islam, por Ibn Battūta; título original árabe

تحفت النزّر في غرئب المصار و عغائب السفار

(Tuhfat al-nuzzur fi gara'ib al-masār wa cagā'ib al-safār; Gift of curious people about exotic things and marvelous trips); introduction, translation and notes by Serafín Fanjul and Federico Arbós, in 794 pages; Editora Nacional; Madrid, 1981.

[11] Una de almogávares, by Arturo Pérez Reverte; article published in the Suplemento dominical "El Semanal" of May 29th, 2005.

|