|

Initial Spanish version: Tuesday April 28th, 2009

ROMAN AQUEDUCTS IN HISPANIA

English version's last updating: Sunday April 28th, 2024

Note: In this work we use the word "aqueduct" in the strict etymologic sense of the word, meaning "water duct", and not necssarily meaning canal over a succession of more or less impressive arcades.

Signs, notes & abbreviations: The sign §, usually reserved to indicate paragraphs, is used here to indicate the number of the hydraulic structure inside each chapter; the traditional English spelling Saragossa (in Latin, Cæsaraugusta) is preferred to Zaragoza; TM abbreviates 'municipality'; PK, kilometric point; EF, 'railway station'; "comarca" is translated as 'district'; "acequia", a canal or ditch generally destinated to irrigation is kept in Spanish, being rather specific; "azud" is translated as 'weir'; "albufera" is translated as 'lagoon'.

Transcriptions from Arabic: ŷ transcribes the consonant "ŷin", phoneme inexistent in modern Spanish, but very similar to French or English "j"; the superindex "c" transcribes the consonant "cain", phoneme inexistent in Indo-european languages; long vowels are shown super imposing a trait over the corresponding short vowel. The alif maqṣūra is transcribed "à", as usual.

Coordinates: in the Iberian Peninsula has just been introduced a new cartographic Datum for the coordinates UTM (Universal Transverse of Mercator), which means new formulæ to convert the geographic spherical coordinates to UTM cartesian coordinates. As in this website UTM coordinates of many points were included, now I aggregate to each coordinate of datum ED50, valid at the date of the first redaction, the equivalent coordinate in the new Datum ETRS89.

Extract

Deliberately omitting, as well known and amply studied, the aqueducts of Tarraco, Segovia, Emerita Augusta, Sexi/Almuñécar, here are treated, with varying depth, 43 other hydraulic structures, of which three are waterwheels of a later age, while the also later artifice of Juanelo is unique in its design. The Roman origin is not contrasted in § 7, § 13, § 15 and § 17.The § 13 and the § 18 refer to water reservoirs, with no aqueduct known. The same can be said from Chapter III, § 1.

The § 12, the § 15 and the § 17 are catchment weirs. In the § 15, although the canal is modern, an ancient one must clearly have existed. From § 17 is preserved the medieval mill it fed. If the weir is Roman or not, that’s to be proven by archaeology.Furthermore, in my opinion, given the magnitude of the aqueduct of Peña Cortada, § 19, in the Comunidad Valenciana’s district of Los Serranos - also omitted in (1) -, it deserves more widespread knowledge.

For an overview of the entire Roman Empire the reader is referred to the excellent book cited in the literature (1), a work which, however, includes only eight Roman aqueducts in Hispania: Tarraco, Segovia, Emerita Augusta, Sexi/Almuñécar, Segobirices/Segóbriga, Calagurris/Calahorra, Toletum/Toledo and Gades/Cádiz.

In May 2013, I found the existence of an advance of the doctoral thesis of Juan Carlos Castillo Barranco and Miguel Arenillas Parra Las presas romanas en España. Propuesta de inventario (Roman Dams in Spain. Inventory Proposal). The text can be seen in the website

www.seprem.es

My articles are rather informal, though always trying to be accurate. No help from any institution was received. They span to the entire Roman Hispania.

Index

Aqueducts will be grouped by Conventvs Ivridici, focusing on new or lesser known aspects:

I-Conventvs Ivridicvs I Lvcensis

§ 1.- Water supply to Lvcvs/Lugo

Go to Chapter I

II-Conventvs Ivridicvs II Astvrvm

§ 1.- Water supply to a Astvrica Avgvsta/Astorga

Go to Chapter II

III-Conventvs Ivridicvs III Bracaravgvstanvs

§ 1.- Water supply to Bracara Avgvsta/Braga (Portugal)

Go to Chapter III

IV-Conventvs Ivridicvs IV Clvniensis

§ 1.- Water supply to Clvnia Svlpicia § 2.- Acueducto del Chorrillo en Flaviobriga/Castro Urdiales

Go to Chapter IV

V-1-Conventvs Ivridicvs V Cæsaravgvstanvs: Water supply to Cæsaravgvsta/Saragossa

§ 1.- Canal Alavn/Alagón-Salduie/Saragossa) § 2.- Weir, canal and inverse siphon of Cæsaravgvsta/Saragossa § 3.- Dam of Muel (Saragossa).

Go to Chapter V-1

V-2-Conventvs Ivridicvs V Cæsaravgvstanvs: Other hydraulic infrastructures

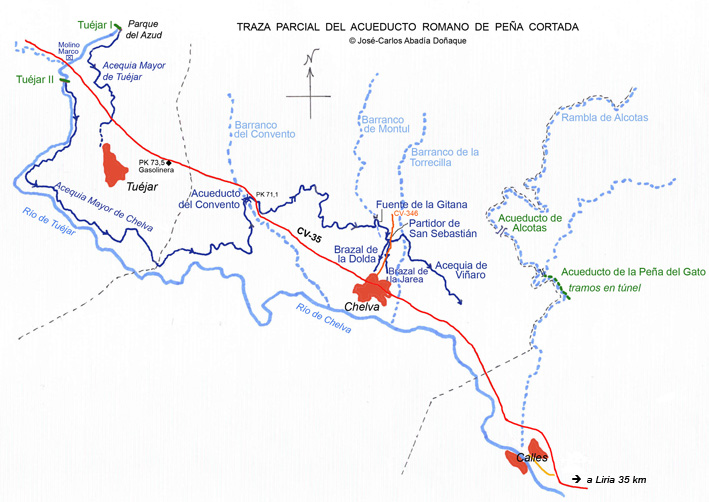

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Alcanadre (La Rioja) or Puente de los Moros § 2.- Aqueduct of San Julián or of Calagvrris § 3.- Rivvs Hiberiensis (Añón, Saragossa) § 4.- Aqueduct of Tarraca/Los Bañales (Layana, Uncastillo, Saragossa) § 5.- Water suplly to Bilbilis Avgvsta (Calatayud, Saragossa) § 6.- Arco de la Mora and Acequia de Candevania (Zuera, Saragossa) § 7.- Acequia de Belchite (Saragossa) § 8.- Acequias de Sástago y Escatrón (Saragossa) § 9.- Norias en el Ebro (Velilla de Ebro and Monasterio de Rueda, Saragossa) § 10 y 11.- Weir and y canalizations of Rané, and dam of Las Azubias (Saragossa) § 12.- Aqueduct of Quicena (Huesca) § 13.- Weir of Abrisén or weir of Fañanás (Huesca) § 14.- Aqueduct Albarracín-Cella (Teruel) § 15.- Weir of Agiria (Villafranca del Campo, Teruel) § 16.- Dam of Monforte de Moyuela (Teruel) § 17.- Aqueduct of Peña Cortada (Valencia) § 18.- Aqueduct of San José (La Vall d'Uixó, Castellón) § 19.- Aqueduct of Andelos (Mendigorría, Navarre).

Go to Chapter V-2

VI-Conventvs Ivridicvs VI Tarraconensis

§ 1.- Water supply to Tarraco/Tarragona

Go to Chapter VI

VII-Conventvs Ivridicvs VII Carthaginensis

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Carthago Nova § 2.- Aqueduct of Toledo § 3.- Artifice of Juanelo (Toledo) § 4.- Dam and Aqueduct of Consabura (Consuegra, Toledo) § 5.- Aqueducts of Baeza (Jaén) § 6.- Aqueduct of Valeria (Las Valeras, Cuenca).

Go to Chapter VII

VIII-Conventvs Ivridicvs VIII Emeritanvs

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Augustóbriga of the Vettoni (Bohonal de Ibor, Cáceres).

Go to Chapter VIII

IX-Conventvs Ivridicvs IX Scallabitanvs

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Conimbriga (Condeixa-a-Velha, Portugal) § 2.- Acueducto de San Sebastián o Arcos do Jardim Botânico (Coimbra, Portugal).

Go to Chapter IX

X-Conventvs Ivridicvs X Pacensis

§ 1.- Aqueduct of la Plata (Évora, Portugal).

Go to Chapter X

XI-Conventvs Ivridicvs XI Hispalensis

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Hispalis - Išbīlīa / Sevilla § 2.- Acueducto de Itálica (Sevilla) § 3.- Aqueduct of Onvba AEstvaria - Awnaba Huelva,

Go to Chapter XI

XII-Conventvs Ivridicvs XII Cordvbensis

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Valdepuentes § 2.- Acueducto de Domiciano § 3.- Acueducto de la Fuente Dorada § 4.- La noria Albolafia.

Go to Chapter XII

XIII-Conventvs Ivridicvs XIII Gaditanvs

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Gades/Cádiz § 2.- Acueducto de Bælo Clavdia(Bolonia, Cádiz).

Go to Chapter XIII

XIV-Conventvs Ivridicvs XIV Astigitanvs

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Egabrvm (Cabra, Córdoba).

Go to Chapter XIV

The attached map shows the division of Hispania attributed to Augustus, with the estimated surfaces of the fourteen Conventvs Ivridici, which lasted for centuries. Their grouping into provinces, however, was modified over time.

Hispania divided by Augustus (some authors attribute it to Tiberius) in fourteen Conventvs Ivridici,

grouped into three provinces

---oOo---

Conventvs Ivridicvs I Lvcensis

I-AQUEDUCTS IN THE CONVENTVS IVRIDICVS I LVCENSIS

In this Conventvs was found the Finis Terræ, that is the Northwestern end of Hispania, ans also, near Brigantivm, the most imposing lighthouse of the Roman West: the so called Tower of Hercules.

Its capital city, Lucvs, today's Lugo, was surrounded of a wall only in the Third Cantury AD.

Lugo: an stretch of the wall's topway

Its place name reappears in diverse points of Western Europe, for example, in Luco de Jiloca (Aragon), in Lugdunum Batavorum (Leyden, the Netherlands), en Lugdunum Gallorum (Lyon, France), en Lugdunum Convenarum (Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, France), en Ravena (Italy) ... always alluding to the Celtic god Lug. Romanization asked providing thermæ, and though a balneum existed in Lvcvs outskirts, by river Miño, -still visitable- an urban aqueduct remained indispensable.

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Lvcvs Avgvsti/Lugo

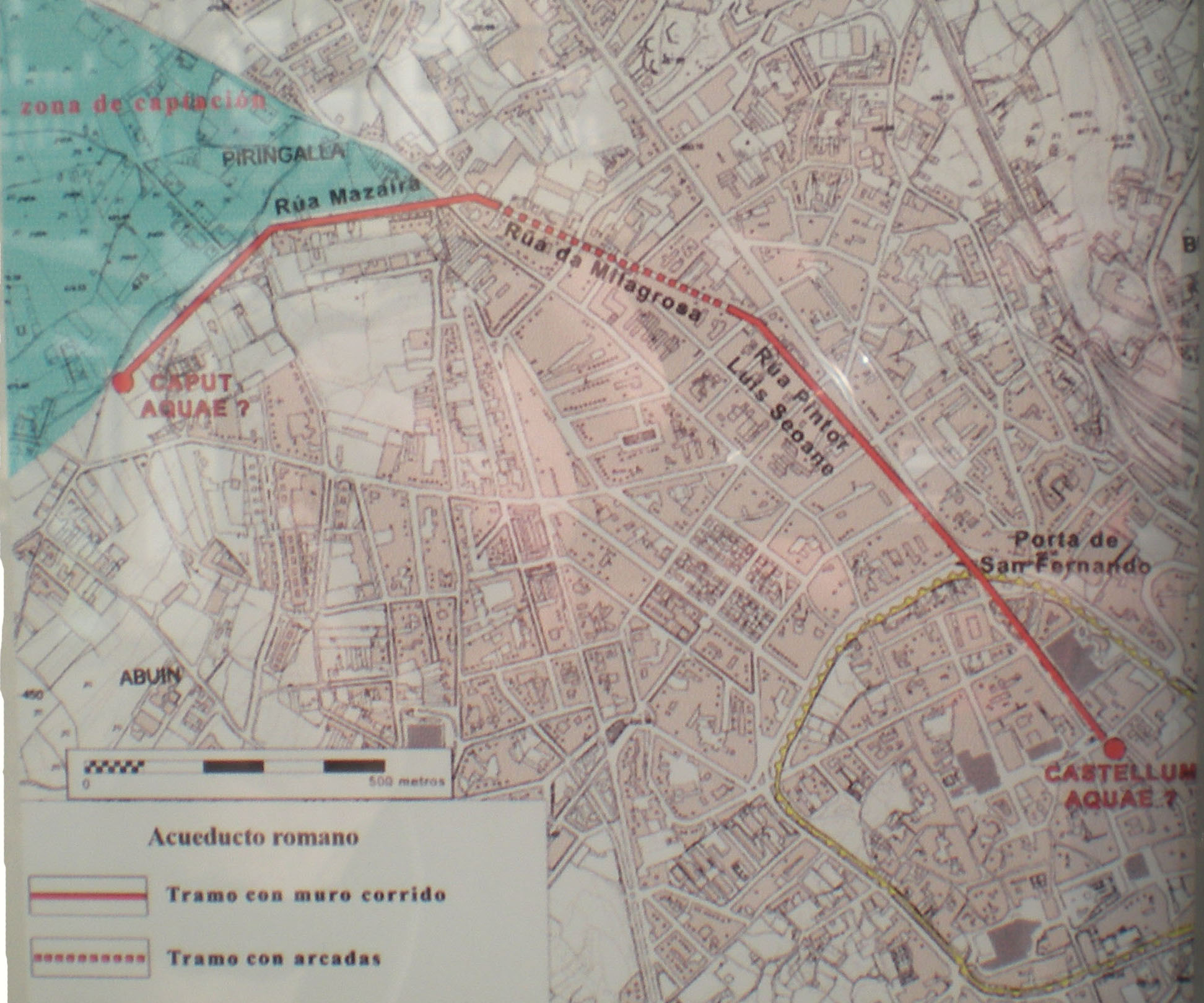

Outline of the aqueduct

It took water from several springs in the Agro do Castiñeiro and, with an specvs scarcely 30 cm wide, it described a turn when arriving at present day's Rúa Mazaira. Following the said rúa, it crossed today's street whose name remembers Queen Juana de Aragón y de Castilla, and followed straigtforward to the point

of coordinates: z=466; 43.920329º N; 7.571673º O; X=614 668, Y=4 864 016 (Datum ETRS89). There, the mentioned Rúa Mazaira, and also the aqueduct, performed a new eastwards turnabout, corssing present day Camino Real in z=464; 43.020426º N; 7.568058º O; X=616 677, Y=4 764 078 (Datum ETRS89), and followed the same outline till arriving to Rúa da Milagrosa, punto: z=466; 43.020879º N; 7.567528º O; X=616 720, Y=4 764 129 (Datum ETRS89).

In brief: the aforementioned geographical coordinates, reduced to coordinates UTM (Datum ETRS89) are, respectively:

X=614 668, Y=4 864 016

X=616 677, Y=4 764 078

X=616 720, Y=4 764 129

The aqueduct turned again in this crossroad so as to follow the said Rúa da Milagrosa, passing before the church of this Marian advocation, and followed straighforward till crossing calle Julia Minguillón. A short elevated stretch was required for saving the slope in taday's plaza de la Milagrosa Foundation slabs have been found measuring 1.20m saquare, separated 2.70 m,; therefore, the existence of of stone arcades was supposed. It is indeed a likely supposssition, but nothing bars that the modes flow passed in wooden stretches, as in Tarraca (tady's Los Bañales in Layana, Aragon); see in thei ssame study Cahpter V-2, § 4). The maximum height of the waterbed over the land in Rúa da Milagrosa was estimated in scarcely 4 m.

Outline of the aqueduct according an informative poster

Since crossing calle Minguillón, there is an outline cahnge pointing to Rúa Seoane, and prolonging its straght direction we should reach the city's walled enclosure by the gate called Puerta de San Fernando or Puerta del Príncipe Alfonso (alluding to the son and successor of Queen Isabel II). A great inscribed slab remebers the visit of King Juan Carlos with occassion of circa the bimillenary of the foundation of Lvcvs Avgvsti, datable ~15 a BC, just at the end of the Cantabrian wars.

Puerta de San Fernando

Under the arcade, to the left, can be seen the white façade and the tower of San Froilán

Great inscription by the Puerta de San Fernando remembering the visit of King don Juan Carlos I.

ANNO·CIRCA·BISMILLESIMO·POST·CIVITATEM·A·CAESARE·AVGVSTO·CONDITAM

IOANNES·CAROLVS·HISPANIARVM·REX·ET·SOPHIA·REGINA

MOENIA·LVCENSIA·A·ROMANIS·EXSTRVCTA·

PVBLICIS·IMPENSIS·NVPER·RESTITVTA·FELICITER·INVISER-(VNT?)

IVLII·A·D·MDCCCCLXXVI

(At about the year two thousandth after the foundation of the city by Cesar Augustus,

Juan Carlos, King of the Spains, and Queen Sophia,

inspected

the fortifications of Lugo by the Romans constructed,

with public money recently restaurated most happily.

July, Anno Domini 1976.)

Hallazgos en la plaza de San Marcos: consecuencias

Al remodelarse en 2011 la referida plaza, que se extiende delante del pazo o palacio de la Diputación Provincial, se descubrió un tramo de acueducto en buen estado de conservación, cuya alineación prolongaba con gran exactitud la que acabo de referir. Dicha alineación, que forma un ligero ángulo con la fachada del palacio, solamente puede alcanzarse desde la puerta de San Fernando intersectando el sólido edificio del antiguo Hospital de San Juan de Dios y su iglesita anexa de San Froilán

Plaza de San Marcos

At the right of the picture, the Palace of the Diputación Provincial

Plaza de San Marcos: Visor of a fragment of the aqueduct

Could this building be founded over the ancient castellvm acqvæ? If so, it would occupy a position similar to the castellvm aqvæ of Conimbriga (present day's Condeixa-a-Velha, Portugal; see in this same study Chapter IX, § 1). I consider preferable this proposal to supposing the castellvm acqvæ in today's Plaza de Santo Domingo, where a water cistern has been found, its dimensions rather meager for the said purpose.

Till here, the Roman aqueduct would reach a length of ~2.200 m.

Biy I think that there was more aqueduct. To this effect, further on from the buildings block closing the SE side of Plaza de San Marcos, the straight outline passes through (or under) the door nº 9 of Plaza de Santo Domingo, only to follow soon the long Rúa do Progreso (o Progresso).

Continuation of the aqueduct under Rúa do Progreso?

This street inflects at its end when leaving at its left (that is, Esatwards) the Rúa das Noreas (Waterwheels's street). Given this place name, and given the geometric -and thus incontesatble- fact that the said Rúa do Progreso performs in the network street of Lugo the function of a hip line in a rrof, audemus dicere (we dare to say) that the aqueduct would probbaly follow along all the said Rúa do Progreso. And from it would derivate branches to reight and left sides, thus being able to supply r¡the totality of the walled precinct.

The athanors of Bishop Iquierdo Tavira

This prelate occupied Lugo's see since 1748 until his death in 1762. Notable urbanistic improvements he promoted, but our interest is here in the rehabilitación of the Roman aqueduct. To this purpose he ordered some athanors to be made, inspired in much older ones, that we shall see in Flaviobriga/Castro Urdiales (Chapter IV) and in Gades/Cádiz (Chapter XIII). He was thus in line with similar rehabilitation iniciatives already done in several Portuguese cities, as in Æminivm/Coimbra and in Pax Ivlia/Beja, realizations to be seen in this Article, in the Chapters dedictaed to their respective Conventvs Ivridicvs.

Remains of an Iseum

Few meters from the cathedral's apse, a visor allows a sight of a little pool, discovered by archaeologists at shallow depth. Initially, it was supposed to be a baptisterium. Nevertheless, camparing it, for instance, with the Iseum of Bælo Calvdia<, and with other well known ones, we are are no doubt before the pool of another Iseum: there was in Lucvs then, a temple to goddess Isis. Linkig these data to the Egyptian remains found out years ago in the cript of the Basilica of Our Lady del Pilar, in Saragossa, we can imagine the extension attained in Hispania by the cult to Isis, already attested in Pompeii as well as in Rome itself, in the Camp of Mars.

Visor near the apse of Lugo's cathedral

showing the pool of the ancient Iseum

Another notable Iseum ws recently reconstructed in Hungary. Man's names as common even today in the Hispanic world as Isidoro and Isidro (worshipper of Isis), are also remembrances of that cult, whose main sanctuary stood in the island of Filæ, in Asswan (Egypt).

Return to Index

---oOo---

Conventvs Ivridicvs II Astvrvm

II-AQUEDUCTS IN THE CONVENTVS IVRIDICVS II ASTVRVM

The imposition of the Pax Romana was followed in this Conventvs Astvrvm by the massive exploitation of the gold of Las Médulas in the benfit of Rome. Legion VI Victrix settled - since about year 29 BC - nearby, and its fortified camp originated the city of León. But the main receptor of the gold extracted from Las Médulas was Astvrica, that became capital of the Conventvs Astvrvm, apparently sometime between the reigns of Claudius and Vespasianus. Its decadence derived from the exhaustion of the gold of Las Médulas.

§ 1: Water supply to Astvrica Avgvsta/Astorga

Nothing is known of the Roman water supply.

Return to Index

---oOo---

Conventvs Ivridicvs III Bracaravgvstanvs

III-AQUEDUCTS IN THE CONVENTVS IVRIDICVS III BRACARAVGVSTANVS

The doubtlessly Celtic Bracara became soon the most Romanized city of Northwestern Hispania; that is why it enjoyed the since ~14 BC the rank of capital of the IIIrd Conventvs Ivridicvs. Furthermore, when at the end of the IIIrd Century, Emperor Diocletianus reorganized the Empire, he dismembered from the enormous Provincia Tarraconensis its three most Western Conventvs Ivridici, creating with them the new Provincia Gallæcia, and granting the rank of capital city to Bracara, that was endowed with the corresponding Provincial Forum and all the rest of the capitaline infrastructures. And when, centuries later, in the Middle Ages, was born the Kingdom of Portugal, this Conventvs belonged to it from the very first moment, and till our days. The limits of the modern Galicia, in Spain, are quite different to the ones of the Roman province of the same name.

§ 1.- Water supply to Bracara Avgvsta/Braga, Portugal

A Roman therma has been found, that would have not functioned without an aqueduct.

Braga's subsoil is rich in water, and in the Middle Ages the supply did not present main problems. An important advance in the matter of water supply is owed to Dom José de Braganza, archbishop of Braga (1741-1756), who intended to follow in this the example of his brother, the King of Portugal Dom John V, whoe order the construction in Lisbon of the Aqueduct of Aguas Livres. The watertaking promoted by the Archbishop tokk water from the Sete Fontes. The 'cuniculi', the convergent galleries and all the framework of these fountains is doubtlessly Roman. The syistem supplied yet in 1934 nothing less than half a million of liters daily. The Roman ancestor of this aqueduct would be the supplier of the public thermæ found in the Alto da Cividade. In this site of high archaeeologic interest have been found, apart of the said thermæ, and the ruins of the Roman theater, the remains of a settlement of the Final Bronze.

Outline of Aqueduct of the Seven Fountains

The Seven Fountains have circular shape, coverd by a vault, all that carefully executed in carved stones. The main waterduct comes from the first spring (in Portuguese, mãe d'agua) in 'cuniculus', and comes receiving differente affluents, also in 'cuniculus', till arriving to Arial, where there was another spring. Sorrily, this one and part of the 'cunículus' were destroyed, the victims of a building operation. The little canal goes on parallel to Via A18 of the Itinerary of Antonino along Rúa do Arial, Largo do Monte de Arcos, Rua de Sao Vicente, Rua dos Chãos, till present day Largo de San Francisco. From there it was distributed to all the city of Braga. The system supplies yet, for example, the fountain of the Largo do Paço, and to the fountain of the Largo Carlos Amarante.

Probable aqueduct procedent from river Ave

Indeed plausible is the hipothesis of this second watertaking, that would catch water in a weir on river Ave, placed where was built, already in the XXth c., the dam of Ermal, as well as a hydroelectric. Archaeology has not found up to date remains of this second aqueduct, but is suggestive the hipothesis of an underground duct as the one that supplied Conimbriga.

Granite athanoras were found in Braga, similar to the ones of Lvcvs/Lugo, Flaviobriga/Castro Urdiales y Gades/Cádiz (See the respective Chapter I §1, Chapter IV §2 and Chapter XIII §1) - just to mention only aqueducts in Hispania -, as well as ceramic athanors.

Connexion of Bracara Avgvsta/Braga with Cæsaravgvsta/Saragossa

In the time of the Tetrarchy, a noble maiden of Bracara Avgvsta, called Engratia, accompanied of her uncle Lupertius and of a brilliant retinue, set to travel (no doubt that the beginning of her trip would follow Via A18 of Antoninus) towards Gallia Narbonensis to marry there her bethroten. At her passage for Cæsaravgvsta she angrily reproched to pretor Dacianus the pityless way in which he persecuted Christians. She was tortured in barbaric way, and her companios were sacrificed.

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens, distinguished official of the Empire under Theodosius I, Augustus of the East (378-392), and also of the West (392-395), and apparently born in this last city, described in the 200 verses of Chant IV of his poem Peristephanon the terribles tortures applied to Engratia, enumerating the names of her companions of martyrdom.

Here is the first stanza:

1 Bis novem noster popvlvs svb vno

2 martyrvm servat cineres sepvlcro,

3 Cæsaravgvstam vocitamus vrbem,

4 res cvi tanta est.

(Our people keeps under a sepulcher

the ashes of twice nine martyrs,

we call Cesaraugusta the city

in which such case is).

Verses 53 to 60 again set as 18 the number of martyrs:

53 Tv decem sanctos reveres et octo,

54 Cæsaravgvsta stvdiosa Christo,

55 verticem flavis oleis revincta,

56 pacis honore.

(You ten saints reveres and eight,

Cesaraugusta studious of Christ,

temple of guilded oils girded,

in honour of peace.)

57 Sola in occvrsvm nvmerosiores

58 martyrvm tvrbas Domino parasti,

59 sola praedives pietate mvlta

60 lvce frveris.

(Alone you prepared numerous

mobs of martyrs at the passage of the Lord,

alone you, rich in piety, with much

light will enjoy.)

These verses allude to the noble Engratia:

109 Hic et Encrati recvbant tvarvm

110 ossa virtvtvm, quibvs efferati

111 spiritvm mvndi, violenta virgo,

112 dedecorasti.

(Here, oh Engratia! rest of your

virtues the bones, with which to the furious

world of the spirits, violent virgen,

you decorated.)

The 3rd of November of year 592 the II Council of Saragossa instituted the festivity of the Innumerable Martyrs (thus was interpreted by the Council the expression numerosiores martyrum turbas of verses 57 and 58). The crypt of the Basílica ofe Santa Engracia, in Saragossa, keeps up to day the memory of these facts, preserved in the Mozarabic liturgy each 3rd of November. (Ver www.basilicasantaengracia.es)

Return to Index

---oOo---

Conventvs Ivridicvs IV Clvniensis

IV-AQUEDUCTS IN THE CONVENTVS IVRIDICVS IV CLVNIENSIS

Celtiberian Clunia

Clunia was an important Celtiberian city, from the group of the Arevaci. Sertorius was besieged there by Pompeius the year 75 BC, but the Celtiberians of the area forced the lifting of the siege. Three years later, after the assasination of Sertorius, Pompeius would destroy this city, like he did with so many others, and he did so thoroughly that the Celtiberian city was forgotten. It probably spreaded over the Alto del Cuerno, that overlooks the confluence of rivers Arandilla and Espeja, in front of Roman Clunia, by Peñalba de Castro (TM of Huerta de Rey).

Coins of the Celtiberian Clunia

This city minted bronze and silver coins, whose reverse displays always the doriphorous rider and the legend KoLOUNIAKu in Celtiberian script. In the obverse they display a manly beardless face. It is astonishing the obstinacy in defining these coins as 'Iberians', and as 'Iberian' its rider.

KoLOUNIAKu in Celtiberian signary. The first and last signs are syllabic.

Más detalles numismáticos en Capítulo V-2, § 2.- Acueducto de San Julián o de Calagurris, y más ampliamente, en mi blog http://salduie.blogspot.com, artículo «Mediana ¿ceca celtíbera?».

Roman Clunia

The Roman Clunia, written Clvnia, was built over a 'muela' that, from its more than 1,000 m over sea level, is a natural fortress that dominates the surrounding landscape, reason why it was never endowed of walls. It was the capital of the Conventvs Ivridicvs of its name, enjoying an spectacular theatre. At the end of Nero's reign (68 AC), Sulpicius Galba, then pretor of the Provincia Tarraconensis, was appointed Emperor by the Senate, what caused great enthousiasm in Clunia, that adopted the surname of Sulpicia in his honor. But the succession process degenerated, and Galba did not survive to it. The infaust year of the four Emperors concluded with the assumption of the Empire by Vespasianus, whose capacity and qualities were very praised. But the Colonia Clunia Sulpicia lost its supporter.

Clunia, destitute of walls, suffered terribly, in the second half of the IIIth century, the invasion of Franks and Alamani, that caused barbaric damages in all the Provincia Tarraconensis. From this time are the hiding of coin hoards found in the ruins of the city.It went on under the Low Empire, and it existed yet under the Wisigoth domination, but it did so as a city without bishop, without mint and without relevance. The Moslems occupied it since year 714 finding no resistance, the Arab fountains mentioning its destruction by Tarik, in his way to Amaya.

General view of the 'muela' over which the Colonia Clunia Sulpicia was built

The village of Peñalba de Castro spreads by the skirts of the 'muela', not far from the Roman theater. In its buildings is evident the use of numerous stones from the ruins of the Roman city. Nevertheless, the place name is kept, transformed, in the village of Coruña del Conde, to the South.

§ 1.- Water supply to Clvnia/Coruña del Conde y Peñalba de Castro, Burgos, Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León

Clunia's underground displays a karstic aquifer that guaranteed inexhaustible water supply to the city, by means of wells. this made useless an aqueduct that, anyway, has not been found. It is very interesting, though, the aquifer spredaing itself under the city. In a cavern was found a priapic little idol and, in different points of the cavity, written over the clayish mud, the names of several urban magistrates. This cavern or caverns ara not open to public visits.

Descending to this underground world through wells, and sailing along some stretches, it is being object of investigation by a scientific team of the University of saragossa. Under the patronage of the Diputación Provincial de Burgos, the specialists surevy and scan the cavity, so as to establish correspondences with the wells that, outside, appear closed after centuries of oblivion.

§ 2.- Aqueduct of El Chorrillo in Flaviobriga/Castro Urdiales, Comunidad Autónoma de Cantabria

The name Flaviobriga, whose ending -briga is quiet Celtic, being also kept, for example, in Arcobriga or in Munébrega, both in Aragon, was granted to it by Emperor Flavius Vespasianus, once consolidated in in power after the crisis of the Four Emperors.

In Castro Urdiales it is known with the name of El Chorrillo an old water duct, built with dovetailing stone athanors. The athanors were made out of parallepipedic blocks of about 45 cm of base and 33 cm high, with a rounded edge, and a central longitudinal hole of about 11 cm of diameter. The dovetailing, sealed with mortar, prevented any water loss. Today someones are missing. This kind of duct was also used in the aqueduct of Cádiz (See Chapter XIII), where the the stretches built with atanors, that are bigger there, were reserved to the sections under pressure. There were also some athanors in the initial stretch of the aqueduct of Bælo Clavdia (31).

Due to the strong leaning landscape, losing pressure chests (spiramina) were built along the aqueduct. Twelve of them have survived, though maybe there were more.

Phisical surroundings of Castro Urdiales

The port P would have been in the past the Portvs (S)amanvs cited by Plinius

In green, layout of the aqueduct, indicating the numerals of the chests

In blue, the course of the creek nearby

Outline description

What we see today (2014) are the remains of the 1806 reconstruction, careful indeed but not perfect, in which the original athanors were reused, laying them over a bed of bricks, and wrapping the whole in a mortar embedding little stones. It seems that some athanors were set turned over their axis, if we compare them to the ones used in Cádiz. The whole is refurbished as a promenade, with abundance of explanation posters, not all of them in good state.

Water duct of Eel Chorrillo: athanor turned over

Water duct of El Chorrillo: Fountain of 1806

Water duct of El Chorrillo: chest (arqueta) X, vista desde aguas abajo

Water duct of El Chorrillo: chest (arqueta) XII

It took quite probably its water from a spring still esxisting al about 200 m of the confluence of creeks Aranzal and Miranda. It crosses through a concrete tunnel under the building Flavia XXI, of peculiar semicircular layout. Chest I coincides with a turnover of the lining. Chest II, very nearby, is a decantation cistern. By it there is a little arcade beginning an old looking tunnel, for a creek that flows parallel to the aqueduct, and by its left side. The outline of the aqueduct is not a straight line, rather describing several turnovers. The tunnel is not a long one, and the creek reappears soon. Then it s crossed by the small bridge of San Lorenzo, of the XVIIIth Century, according to the possters, but it looks older. The last chest of the aquedcut is number XII, placed already near the junction of Bajada del Chorrillo with Calle Leonardo Rucabado. The total length, from chest I to the lower point still extant, is of ~280 m, including the ~7 m downstream chest XII.

Legal protection

The infrastructure is protected by Decree of the Government of Cantabria, published in the BOC of Tuesday 21 of March of 2006.

Return to Index

---oOo---

V-WATERWORKS IN THE CONVENTVS IVRIDICVS V CÆSARAVGVSTANVS:

ENDEMIC WATER SHORTAGES

Solid proof of the secular low rainfall in most of the area outlined, are the numerous ancient irrigation infrastructures, as well as the peculiar urban supplies.

Proof also of the scarcity of water flows is the profusion of legal texts intended to optimize the management of the few available flows. Paraphrasing the Latin expression corrvptissima republica, plurima leges we could say: most scarce water, proliferation of rules. The abundant legiferation pretends to control and optimize shortages.

V-1-Conventvs Ivridicvs V Cæsaravgvstanvs: Water supply to Cæsaravgvsta/Saragossa

V-1-Conventvs Ivridicvs V Cæsaravgvstanvs: Water supply to Cæsaravgvsta/Saragossa

§ 1.- Canal Alavn/Alagón-Salduie/Saragossa

Information about this acequia (in Latin, rivvs), about eighteen kilometres long, indeed in many ways an interesting work, including the oldest document concerning Hispania's water supply, can be found in Spanish in (6). A second edition in colour, also in Spanish, in:

http://traianvs.net/.

And an English version in my blog:

http://salduie.blogspot.com

My basic proposal in all these texts is that the canal (rivvs) alluded to in the bronze written in Latin and dated in the Ides of May of the year 87 BC, initially known as Tabula Contrebiensis, then as Botorrita-2, cannot differ much in its layout from the Acequia de la Almozara, still in service.

The bronzes Botorrita-1, Botorrita-3 and Botorrita-4 are all written in Celtiberian language, using a Celtiberian variant of Iberian signary. All three of them were found in the whereabouts of Contrebia Belaisca, on the banks of the Huerva, very close to present-day Botorrita. In (5), focusing in Botorrita-3, are also reviwed the previous two bronzes. Recently, it has been published (7) a well-documented translation into Spanish of the Celtiberian text of Botorrita-1, translation proposed by Patrizia de Bernardo.

Since centuries ago are known numerous Celtiberian coins minted in this city, with a manly face in the obverse, and a rider called "Iberian" -indeed, Celtiberian- and with the text CoNTeBaKoM·BeL in the reverse.

---oOo---

§ 2.- Weir, canal and inverse siphon of Cæsaravgvsta/Saragossa

I already included information en (6) over this notable yet quite unknown infrastructure in § 1 of this Cahpter V-1. A quite enlarged edition, though twice extracted by reasons of space, was published in (6) bis.

I intend to include soon the complete, non abbreviated, Spanish text.

---oOo---

§ 3.- The Acequia of Muel, towards Contrebia/Botorrita?

In Muel, by the Huerva, at about 30 km upstream from Saragossa, there is a Roman dam, whose vessel is totally earthened since centuries ago. Upon its top stands a chapel to Our Lady, with paintings by Goya.

Roman dam on the Huerva in Muel (Saragossa)

By its vertical downstream face, just cleared displaying its stone blocks of typical Roman making, there is a pond and a nice park. Then, downstream in the left bank, still stand up the ruins of a former watermill, whose details were published by Carlos Blázquez (fascicles edition in El Periódico de Aragón).

The acequia is carved in the rock in its first meters, and its layout and real purpose are still unknown, as no continuity to Contrebia Belaisca/Botorrrita has been found. Therefore, the exclusive purpose of the dam might just be the regulation of waters of the Huerva, so as to guarantee an adequate supply to Cæsaravgvsta.

See more about the possible purpose of this water infrastructure in (12).

Return to Index

---oOo---

V-2-Conventvs Ivridicvs V Cæsaravgvstanvs: Other hydraulic infrastructures

V-2-Conventvs Ivridicvs V Cæsaravgvstanvs: Other hydraulic infrastructures

§ 1.- Aqueduct of Alcanadre (La Rioja)

The place name Alcanadre, also applied to Alcanadre River, a tributary of river Cinca, in Aragon, comes from the Arabic al-Qanatir, plural of al-Qantara, "the bridge", and means "the bridges", "the arches", "the aqueduct", according to Materiales para el estudio de la toponimia árabe (Materials for the study of Arabic place names), by Elías Terés; Madrid, 1986; pág. 217. The Rioja's town of Alcanadre owes therefore its name to the aqueduct that ran in its vicinity, known as "Puente de los Moros" (Moors' Bridge). It indeed crossed the Ebro, and the place name is as Arabic as the ancient street layout of Alcanadre, formerly round-shaped.

Moreover, just as the Roman roads marked often the boundaries between municipalities, this aqueduct disclaims here TM of Alcanadre from TM of Lodosa, and therefore La Rioja from Navarre.

Object of the canal

The grand Iberian river’s crossing was part of a work of extraordinary ambition, designed to transfer flows from the left bank of the Ebro to the right bank, as the Romans did also in Cæsaravgvsta, and how recently was done between Pradilla and the Loteta reservoir in Aragon.

Tentatively it was justified for the water supply to Calagvrris (1), although its level invalidates this hypothesis.

Now, after the discovery of San Julián’s canal (See § 2), an agricultural purpose is proposed, given its considerable section (specvs of 1.50 m), and the resulting flow capacity (2.88 m3/s, according to (2).

Origin of the canal, and its display on the left bank of the Ebro

Flows from river Odrón were catched shortly downstream of its confluence with river Linares, near Lazagurría (Navarre), where the term "El Charcal" (The Puddler) seems suggestive. In addition, ancient stones have been discovered embedded in the concrete of a modern weir. (See (2)).

The canal ran parallel to the northern margin of present day road NA-134, entering La Rioja, where the road becomes the LR-134. After some hectometers, to reach the point X = 573 106, Y = 4 696 743 (Datum ED50); X=572 999, Y=4 696 534 (Datum ETRS89), the channel describes a 90º turn to the right, crosses the LR-134, and points towards the Ebro, to where now lies the left abutment of the weir of modern Canal de Lodosa.

Thirteen arcades are still standing along about 80 m, and the pillars of the ruined arches along another ~ 320 m define a straight alignment from the road above, to the shore of the Ebro in X = 573 487, Y = 4 696 490 (Datum ED50); x=573 380, Y=4 696 281 (Datum ETRS89), at about 520 m of the aforementioned turnabout of 90 °.

According to (2), an unknown number of arches were blown up in this last stretch, its stones to be reused in the works of Canal de Lodosa.

Arcades of the aqueduct upstream the "Puente de los Moros" (Moor's Bridge)

The crossing of the Ebro and the layout on the right bank

Based on data from archaeologist Don Blas Taracena, the crossing of the Ebro was studied and published in (2) by María-Ángeles Mezquíriz, who excavated at both abutments of the disappeared waterbridge, dating it between c. I to c. II AC. The complete disappearance of the arches over the Ebro is most unlucky. I was unable to find the date or the cause of their ruin, the first suspect being Ebro river itself, not excluding an earthqake.

On the right bank of the Ebro are left the remains of an arch of the aqueduct in the point X = 573 646, Y = 4 696 389 (Datum ED50); X=573 539, Y=4 696 180 (Datum ETRS89), which permits an estimate of their total number in one hundred and eight, supposing them all of the same span (4.80 m).

I join thus the proposal to call this colossal work "Aqueduct of the Hundred Eyes".

The height of 5 m of this arch would be, according to (2), the necessary one to make up with the structure of the left bank of the Ebro. At the foot of this remains is the modern catchment weir of Canal de Lodosa (canal being built between 1915 and 1935, but whose extension to Aragon dates after the war 1936-1939), on the right bank of the Ebro. But the Roman canal ran to a quite higher level, so it would have dominated areas that Canal de Lodosa (length: 127 km; flow in the catchment increased recently to 29 m 3/s) can not serve by gravity.

The remains of the aqueduct south of the Ebro were affected by the construction in 1863 of the railway stretch Castejón-Bilbao, from the itinerary Saragossa-Bilbao that between EF Alcanadre and EF Lodosa, located in Navarre, describes a closed curve, sandwiched between the Ebro and the escarpment of the right bank of the great Iberian river.

Archaeological findings in different sections of the aqueduct, which followed a path substantially parallel to that adopted later on for the railway, were published in (2).

Mrs. Mezquíriz dug about 30 m of canal near PK 37 of today’s road NA-123 between Lodosa and Calahorra. The name Murillo de Calahorra suggests, according to the author, the remains of a wall, perhaps Roman. Her hypothesis that the pillars found in the Sorbán area, near Calahorra, would belong to this canal was not confirmed eventually: they would rather belong to the canal studied in § 2.

An untested hypothesis

The place name Alcanadre, and the names Calle de (los) Pilares (Pillars), Calle Trasera de Pilares and Travesía de Pilares, clearly allude to pillars once standing. They are not visible today, but remains could survive hidden inside existing houses between the three mentioned streets.

These pillars could be explained in two ways: first, if once in the right bank of the Ebro, the canal today visible in the left bank had been split in two, and a second branch of the same would turn to the southwest, supporting itself on the side of the small plateau crowned by Fuente del Berro (409 m). Then, and this is pure hypothesis, it would go on demarcating in subsequent sections the present day TM of Alcanadre (La Rioja) and TM of Lodosa (Navarre), until at least the intersection of the boundary with the AP-68 Saragossa-Bilbao.

A second hypothesis: that these pillars belonged to a certainly minor aqueduct, taking waters from the rivulet that flows to the west of Alcanadre.

Possible layouts are pending study.

Far left in the picture, at the other bank of the Ebro, arcades of the «Puente de los Moros»

In the center, the Ebro with the weir of modern Canal de Lodosa

To the right, the railway under its protecting roof

Dimensions

In summary, dimensions are: total estimated length of the canal: 30 km; aqueduct of 108 arches of 4.80 m span; specvs of 1.50 m wide and tellers 0.65 m high; building type: opvs cæmenticivm; estimated flow, assuming a slope of 1 ‰ (one per thousand): 2.88 m 3/s.

---oOo---

§ 2.- Aqueduct of San Julián or of Calagvrris (La Rioja)

Discovery, catchment and layout

It was discovered by Don Hilario Pascual González in the early 1980's.

It catched mountain waters of excellent quality in the Sierra de la Hez, on a spot close to the chapel of San Julián, at a heigth of about 900 meters. The catchment weir and the adjacent sections were swept away by flood waters long ago. These waters supply nowadays the Balsa de Ocón, 1.5 miles from Ruedas de Ocón.

Upper section of the canal, with the gorge below

UTM coordinates: X = 570 303, Y = 4 696 477 (Datum ED50); X=570 195, Y=4 696 268 (Datum ETRS89)

Detail of the upper part of the canal

The canal, underground and covered, outcrops at several points, making it possible to reconstruct the original layout with good approximation.

With a length of about 30 km, it runs about eastwards, passing south of Carbonera, then crosses first the LR-123 road and then the LR-134, nearby La Maja. It then surrounds by the east a hillock, to stick then to the aforementioned LR-134 (Calahorra-Arnedo) to reach the Sorbán rest area. There, next to the site of that former city (VII-V century BC) are preserved several piers of the disappeared aqueduct. The structure is estimated to have had about 3,000 m in length, and would reach Calagvrris at sufficient level to supply by gravity the ancient city (now Raso).

Remains of the old aqueduct to Calagvrris along a modern acequia

Poster showing the layout of the canal of San Julián to Calagvrris

Importance of Calahorra

A project of this magnitude is justified by the importance of this ancient city. There can be no confusion with Calagurris Fibularia, which was nearby Huesca, in Aragon.

KaLAKoRRIKoS coins show on their reverse the Celtiberian doryphoros knight, riding to the right over the aforementioned text.

Text of the Celtiberian coins of KaLAKoRRIKoS

On the obverse, a varonile head, its beard shaved, decorates his neck with a Celtic torque. One dolphin on the left and one on the right classify these coins in the group of “the two dolphins”. Its uniqueness lies in the waning moon with a star.

The city suffered a terrible destruction at the end of the Sertorian wars (70 B.C.), any longer minting in Celtiberian script. It received Baske settlers loyal to Rome, later on adopting the name of Calagvrris Ivlia. The aqueduct would date from imperial times. Calagvrris was home of the famous scholar Quintilianus.

The city was again razed in the fourth century by the invasion of the Barbarians who sacked the provincial capital Tarraco and other cities in the province of Tarragona, such as Cæsaravgvsta.

Then might have happened the destruction of the aqueduct, its remains later reused for other buildings.

During the Andalusi period, the city received, by homophony, the name of Qacala Horra, meaning single or exempt fortification, hence its modern name. That same term also appears in other parts of the Spanish geography, for example, in the isolated fortress that protects the southern abutment of the Córdoba's bridge over the Guadalquivir.

Final incognita

It's left thus to clarify what actually targeted the construction of the imposing Aqueduct of the Hundred Eyes that we have seen in the previous section.

---oOo---

§ 3.- The rivvs Hiberiensis

Background

In 1993, Don Javier Pellicer Benito discovered in the area of Gañarul, (TM of Agón), about 50 km northwest of the city of Saragossa, the fragments of a bronze written in Latin. They were recomposed, then studied and recently published by Francisco Beltrán Lloris, whose authority we refer to (3). The recovered fragments allowed to reconstruct two-thirds of the bronze plate, written in three columns.

The comprehensive edition of the Latin text, with an English translation, is a major contribution to the history of Roman irrigation systems. It includes a map of the central section of the Ebro with the so far known Roman canals, which encourages studies in various scenarios.

Dated under the rule of Emperor Hadrianus, it establishes, with the rank of Lex, rules for the operation of an acequia or irrigation canal named rivvs Hiberiensis between pagvs Gallorvm (Gallur), pagvs Belsinonensis (El Convento, in Mallén?), and pagvs Segardinensis (so far unknown), whose layout remains a question mark until now.

We will address this point here.

First possibility: a catchment from the Ebro

Although it is doubtful that the Roman technique was able to build and maintain an economically bearable weir or diversion dam on the mainstream of the Ebro, that possibility cannot not be ruled out a priori. It seems, however, unlikely that such a technical (and political) feat had not left any literary or historical vestige.

Second possibility: a catchment from river KeILEZ/Queiles

Cascante, along the Queiles, irrigates its pagvs by acequias running on both sides of this river, catched upstream, thus creating an strip of fertile land at each margin.

We knew that Cascante annexed Ablitas, which is too little indeed, and that under this old town runs an acequia. Might it been possible that such a canal had reached Belsino/Mallén? Examining the ground, such a thing would be possible only by drilling a tunnel, from which not vestiges at all have been found.

Third possibility: catchment from the Huecha

Its flow and its heigth are so scarce in the vicinity of Belsino/Mallén?, that a catchement of Lower Huecha seems simply not feasible.

The answer: Segarde

The only flows available are the ones supplied by the Acequia de Sorbán, which comes from the upper reaches of the Huecha and cross by a tunnel the city of Borja; it receives sporadically additional flows collected by the ravine of Arbolitas, and accrued with ravines such as el Lobo, la Albardilla, el Pasmo. They all converge in La Estanca (level 400), where they are stored in winter for use in spring and summer.

La Estanca of Borja

Although the beautiful Mudéjar building was the work of the master builder Antón de Veaxa, from Borja, who built it between 1539 and 1542, it stands over blocks that, by their appearance, might be of Roman origin.

Casa de Compuertas (Watergates House): to the right corner, see old stones

They are also Roman and maybe pre-Roman the foundations of the main building (dating from XVIIth Century) of the Santuario (Shrine) de Misericordia, very dear to the people of Borja.

The Celtiberian character of these sites point to a Celtic sacred forest in full.

On the northern surroundings of La Estanca runs the way Borja-Tudela [1], which saves the ravine Vulcafrailes (Longitude 1º 31' 43" or 1.528611º W; Latitude 41º 54' 15" or 41.904167º N) through an Eye or Arch that stands over blocks of quite a clear Roman appearance.

Ojo or Arch of the Borja-Tudela way over the ravine of Vulcafrailes

This road intersects the alternative way Tvriaso/Tarazona to Cæsaravgvsta, which ran eastwards, judging by the evidence, roughly following the terrestrial parallel (Parallel 41º 54 '30 "; Ordinate Y = 4 540 000) and passing through Cunchillos and also at the north of El Buste and the Muela de Borja. In that stretch, the path would run approximately over the current boundary between the TM of El Buste and TM o Tarazona over more than 3 km.

Both La Estanca and its spillway are at a level close to 400 m, allowing them to cover an area that could never be irrigated directly from the Huecha.

In the photograph, taken in full August, you can see how desertic is the landscape, hence the value it has and has always had water for irrigation.

The Acequia of La Estanca

After a hiatus of about 7 km, the Acequia de La Estanca or Acequia de Villaré, which also follows the same geographical parallel that the said Tarazona-Zaragoza route, marks roughly - even today - the municipal boundary between Fréscano (to the South) and Mallén to about 1 km to the east of the modern Canal de Lodosa.

At that point, distant about 3 km from Mallén, instead of continuing eastwards, both the canal and the inter-municipal boundary make a bend to the southeast, pointing to the hills of Burrén and La Burrena, saving them by the north, heading to Gallur.

Acequias of La Estanca up to the Huecha aqueduct near Fréscano

TM boundaries in dashed

Thus, the southern section of the "Acequia de Villaré" runs leaving to the west the Morredón, after making the boundary between Fréscano and Mallén as described ut supra.

An ancient site was excavated in the hill of El Morredón (level 353), and is documented in the Burrén hill at the other side (433).

However, this whole area has seen modified its network of canals by the impact of the new (from a historical perspective) and great Canal de Lodosa (finished in 1948) that provides flows much more important than those never known by territory analyzed, although at a lower level (around 280). That is why some pumping elevations have been authorized.

This results in a complicated network of canals: some capture of the Huecha, other ones from La Estanca, others from the Canal de Lodosa. This is the only one that provides significant flows, primarily served by gravity, but also to some extent by pumping. (Pumping water, given the systems of energy prices and of agricultural prices, results in excessively expensive production costs.)

Ancient Aqueduct on the riverbed (dry in August) of the Huecha nearby Fréscano

The beautiful aqueduct on the Huecha, a single arch -the river deserves no more-, though now obsolete, must have driven flows in the above-mentioned acequias. Today, these flows pass through a steel siphon under the bed of the Huecha that, as we see, may completely dry in Summer.

---oOo---

§ 4.- Aqueduct of Tarraca/Los Bañales in Layana, near Uncastillo (Saragossa)

Known and repeatedly described from João Baptista Labanha (XVI-XVII centuries).

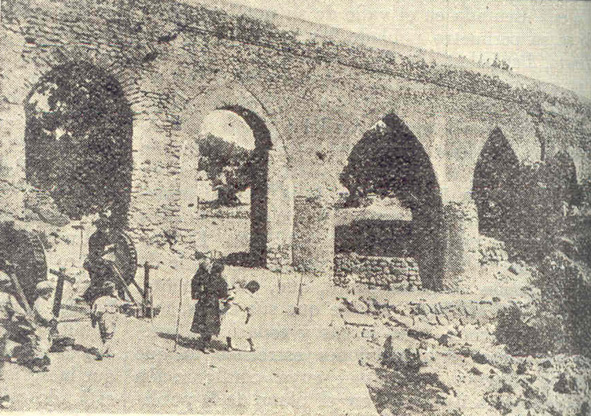

Panoramic view of the remains of Los Bañales aqueduct

Detail of some pillars of Los Bañales aqueduct

In the hill of el Pueyo there are relevant remains, among them enormous stone blocks from a pre-Roman city. The Roman city that stretches at its feet would date from the second half of the first century AD, and was abandoned by mid III century.

"El Periódico de Aragón" of Friday August 6th, 2010 anticipates the news that in the excavations at this site has just been discovered a public building still unidentified, "located in the southern part of what should be the public square of the city" as well as a new section of the aqueduct dug into the rock

The Dam of Cubalmena (TM of Biota) has also been related to the Roman aqueduct, whether as its source or, according to (14), as an intermediate step of regulation and distribution. We look forward to the relevant publication.

Dam of Cubalmena, near Biota (Saragossa)

---oOo---

§ 5.- Water supply to Bilbilis Avgvsta (Calatayud, Saragossa)

Story of three cities

There was a Celtiberian BiLBiL in Valdeherrera, at the confluence of the Jiloca with the Jalón. Just beneath the city of Calatayud, foundation of Muslim era, have just been discovered and recently published the baths of another Roman city called Platea, name as Greek as the city of the same name, famous for the battle in the Medic Wars (See their respective locations on the map at the end of my article Ruta 31 del Itinerario de Antonino, in Spanish, in this same website). And finally, 6 km away in the hillock of Bámbola, there was a Mvnicipivm Bilbilis, since ever known and described, and from 1965 investigated and excavated by Prof. Manuel Martín Bueno, University of Saragossa.

Access to the water

It seems not credible that "complete thermal baths, with hot and cold rooms, with their pools, ... occupying an area of over 500 m2 ... and a source (labrum)" depend only on rainwater, even with supplemental water carriers hauling it from the Jalón, that encircles the foot of the hill.

Yhe city of Municipium Bilbilis, with up to 30 hectares in extent, is stepped down the steep hillside, with the top at elevation709. Across the Jalón, on the right bank, is Huérmeda, whose abundance of springs contrasts with the dryness of Bilbilis, no doubt brought abandoned when its water supply decayed.

I propose that the water supply of Bilbilis could only proceed from Marivella area (next to the former N-II), only with sufficient flow and enough elevation. In that area of Marivella there are numerous villas with swimming pool, and other buildings, all with abundant water. A hypothetical lead piping would certainly have been robbed over the centuries. Would there be left any vestiges?

Bilbilis Avgvsta. To the right of the photo, under the date, see a steep straight path,

where could have been a water pipe

Possible trace of a pipe. Chest first. To the bottom, the Anchis Flats

Detail of an opvs cæmenticivm casket

Portal in Huérmeda on the way to Calatayud. Upstream face

Large stones by the Jalón in point X=617 295, Y=4 581 977, Z=507 Datum ED50); X=617 186, Y=4 581 768 (Datum ETRS89)

Possible layout of a pressure pipeline

To reach the heigth 618, a hypothetical pressure piping had to start from a level not less than 643, estimating, in a first trial, a pressure drop of 25 m, at a rate of 10 m water column per kilometer of pipe (25 m = 10 m × 2.5 km).

The lead pipeline would be initially parallel at the northwest to the N-II-a (azimuth 255 °), and would top the PK 241-a and after having run from the head about 900 m, would turn to the northwest (azimuth 315 °) heading to Bilbilis, always descending (level 621 to level 614).

After passing (level 605) over the tunnel of the LAV (Línea de Alta Velocidad) in Marivella, keeping the same azimuth, would descend gently through the Plana de Anchís (elevation 600 to elevation 550) till the escarpment on the Jalón.

It would cross the river (elevation 510) half a kilometer upstream of Huérmeda, at the point of coordinates

X = 617 295, Y = 4 581 977 (Datum ED50); X= Y= (Datum ETRS89).

Between the change of azimuth and the Jalón, the distance is about 1,100 m.

The venter of the inverse siphon would be in a hypothetical bridge over the river. There, the hydrostatic pressure would not exceed 150 m of water column, about 15 bars, a technically acceptable pressure for lead pipes (fistvlæ plvmbeis) of the time.

The path from Huérmeda has there a curious gate, perhaps reminiscent of a Roman arch that hypothetically would have been in the vicinity.

At the opposite shore, large stones are stockpiled.

From there, continuing a straight alignment, the pipeline would have traced its way up to Bilbilis, reaching its Thermal Baths at level 618, under the principle of communicating vessels.

In the upper stretch, at the point of coordinates X=617 051, Y=4 582 259, Z=570 (Datum ED50); X=616 942, Y=4 582 050 (Datum ETRS89), there is a water collection chest.

The total length of the pipeline, now fully rebuildable, would be only of about 2,500 m.

All dimensions and azimuths are approximate, having been obtained just with an iPhone.

Such an inverse siphon - were its existence be confirmed-, with a height less than the Hellenistic siphon of Pergamon (190 m), would nevertheless exceed the 135 m heigth of the Giers siphon, the largest of the four water ducts to Lvgdvnvm/Lyons, in Gaul (1). (This structure inspired the reverse of the banknote of 5 euros).

It could be analyzed, as was done in Pergamon, if the soil is contaminated with lead compounds, along the hypothetical route of the pipeline.

Were its existence be confirmed, such inverse siphon would merit maybe an special issue of 5 euros banknote!

Ruinous strong house in the foreground (elevation 532).

In the background above (level 629), across the Jalón, the esplanade of the temple of Bilbilis Avgvsta.

Access to the Roman road

Descending the port of Cavero, the Alio itinere ab Emerita (Augusta) ad Cæsaravgvsta, in the direction from Saragossa to Mérida, converges toward the Jalón while leaving Bilbilis Avgvsta to the right.

The via comes down from Marivella by the Planas de Anchís towards the strong house;

in the background, the city of Calatayud.

In the center, saving the pit, the narrow access to the strong house.

In the background, the steel railway bridge of the line Calatayud-Saragossa.

In the background, Calatayud and its orchards, the whole dominated by the castle (Qacalat) of cAyud,

"the strongest fortress of eastern al-Andalus", according to (15), p. 318.

To access Bilbilis from here, a bridge over the Jalón is required

Starting the descent from the strong house to the now missing bridge over the Jalón

On the left bank of the Jalón, in the point X=616 714, Y=4 581782 Datum ED50); X=616 605, Y=4 581 573 (Datum ETRS89), still seen from its right bank boulders, remnants of an old bridge over the river, dominated here by the strong house. This, datable in the XVIIth - XVIIIth c., defends the western entrance with the escarpment of he river, and its eastern entrance by a pit.

It may have been built on the foundations of a Roman fort that once guaranteed the security of this key pathway. Could archeology trace the foundations of the missing bridge, and find out its age?

Strong house dominating the Jalón (hidden behind the reeds)

Large stones, possible remains of the bridge over the Jalón

---oOo---

§ 7.- Arco de la Mora and Acequia of Candevania in Zuera (Saragossa)

Very nearby Zuera, spans an out of service aqueduct, interesting for its rarity, and restored with muito amor.

Initially, I did not include it among the relevant Roman aqueducts, being work -as the sign reads- from the Thagree (Zagrí) - Andalusi period (XIth Century).

However, the existence of possible Roman remains in its environment, justify its inclusion here.

Colorless signpost

Arco de la Mora seen from downstream

Concrete deck, showing its considerable width,

and a nice personal message

The place name Zuera

The place name Zuera comes from the Arabic çuhayra, diminutive of hayyar, stone, rock; therefore, the word means little rock. From there would come "Çuhaira" or "Çuhera", that with the unhappy suppression of the letter Ç, clumsily replaced by Z, became Zuhera, Zufera, Zuera.

It would have reoccupied a former Roman settlement, located in La Recueja (Zuera).

Location

The Arco de la Mora is adjacent to a rest area on the road access to Zuera, crossing the Huerta Chica, just south of exit 316 Zuera-Ejea of motorway A-23, about 25 km north of the city of Saragossa. It spans over a narrow valley cutting the western escarpment of the Gállego valley towards the Qibla.

Deck's UTM coordinates are X=683 576 Y=4 638 591 (Datum ED50); X=683 468, Y=4 638 382 (Datum ETRS98).

Dimensions

The width (4.14 m) of modern concrete deck (not flying over the oldest work) is such that it is not conceivable that the canal occupied it in full. The excessive width would be designed for a service road. This width does not equal a whole number of feet of Aragon of 25.6 cm, nor Aragon's cubits of 38.4 cm. However, it turns out to be almost exactly 14 Roman feet of 0.296 m.

Its length is of 31 steps (about 22 m), and no excavation in the mountain is apparent upstream or downstream. Perhaps, though, an exam with GPR, an economic and non-intrusive technique, might provide surprises.

The deck's elevation is 292 (± 3 m).

Paralelism of this Thagree (of the Islamic Kingdom of Saragossa) aqueduct with a Caliphal one

The disposition, general aspect and dimensions of this aqueduct are very similar - except that the three arches are pointed and not horse-shoe shaped - to the ones of the caliphal aqueduct of Valdepuentes, near Medina Azahara. See Chapter XII-Aqueducts in the Conventvs Ivridicvs XII Cordvbensis § 1.- Aqueduct of Valdepuentes.

The Acequia of Candevania

Parallel to the Arco de la Mora, and between it and the road, i.e. downstream of the valley, runs the big Acequia de Candevania (Can de Bania, Can de Banya, Can de Baña, where "Can" means "house", and "baña" means "bathing", a place name related to Los Bañales), which irrigates all these terms with flows uptaken from river Gállego in the same weir (although in opposite shore) than the Acequia de Candeclaus or Acequia Camarera, at about 8 km upstream, at the height of Ontinar del Salz. However, Candevania runs at a level about 13 m below the deck of Arco de la Mora.

Ancient arch like a "gallipuente", over which passes the Acequia de Candevania

In the background, the Arco de la Mora

Although the Acequia de Candevania has always been considered medieval, some say that this arch or gallipuente could be Roman or even pre-roman (Celtiberian). A second ancient arch, similar to this one, spans itself downstream, near the village, in the Canalillo. It is also reasonably believed that the Arco de la Mora and the windows in the escarpment would be dated later, and that the work remained unfinished at the time. See

www.ayunzuera.com

Acequia of Candevania; in the background, Zuera; on the right, windows on the escarpment

Windows carved into the rock of the escarpment

At a short distance downstream, and at a similar level to the aqueduct deck, can be seen from the road two non-small windows open on the escarpment, which could illuminate a carved tunnel extension of the Arco de la Mora.

Further downstream, it reaches Zuera's houses, where Calle Arenales respects the eventual tunnel alignment and stands substantially horizontal, at a level of 289 (± 3 m), ie, about 3 m (the GPS error margin of ± 3 m, can not be more precise), lower than the deck of the aqueduct.

Aspect before restoration

Historical photographs with the state prior to the restoration of the Arco de la Mora, and the criteria used in this restoration can be seen in

http://sites.google.com/site/zagralandalus/arcodelamora

The authors state a curious and intriguing detail: the existence of a 'mataesquinas', a corner-killer, under the main keystone of the Arco de la Mora. A magical function, anti-demons, is attributed to this feature, which would be further proof of this being a Thagree work, perhaps with Fatimid reminiscences.

Timber corner-killer in the Arch

The photograph contributed with the initial state of the work seems to show a parabolic arch somewhat larger than the vertical piers on which it rests. This widening was ment to ease the setting of the framework.

The parabolic arch and the pointed arch

The parabolic arch of Ctesiphon in Mada'in, about 30 km south of Baghdad, which is actually not an arch, but the vault of the Throne Hall of the Sassanid Kings, a still remaining pre-islamic feature, is the perfect anti-funicular, and may have inspired the pointed arch, which I refuse to designate with the absurd name of "Gothic", since this art has absolutely nothing to do with the Goths.

Arco de la Mora: façade upstream

An unfinished work

In the aforementioned website, the authors wonder about the causes of the stoppage of the work, whose construction date at the time of the Kingdom of Saraqusta/Saragossa (1031-1118). The Numismatic evidence proves that Saraqusta's mint suspended the emissions of dirhems (in Arabic, darahim) since 489/1096 (the year of the Battle of Alcoraz and subsequent loss of Huesca to Aragonese Christian hands) until the year 497 AH, equivalent to 1104 AD (Peter I of Aragon reigned 1094-1104). This suspension points to a silver shortage and economic crisis, circumstances that, as we unfortunately know, tend to cause the stoppage of public and private works.

Possible uptake of a canal feeding the Arco de la Mora

It now remains to find the point of the Gállego where this remarkable and abandoned canal could have had its uptake.

As the deck of the Arco de la Mora is at level 292 (± 3 m), and the Gállego river level up to the shrine of Our Lady of Salz (and approximately the provincial boundary between Saragossa province and Huesca province - district Hoya de Huesca) is the 290, we have just to look for a suitable location upstream of said district and provincial boundaries.

Facing Gurrea de Gallego is the modern catchment weir of Soto (X = 684,572, Y = 4,654,345, Z = 315 (±3 m)). Joining this point directly with the deck of Arco de la Mora, the distance would be 15,785 m, with a slope of 1.4 ‰. (Of course, the path would not be a straight line and the slope would decrease with increasing length). Between this and the weir of La Paúl there is a stretch in which the Gállego licks the western escarpment, which imposes today the necessity of a tunnel for the acequia of about 200 m in length.

One could search around the environment of that weir, or even further upstream, the catchment planned by the unknown designer of the Arco de la Mora canal.

---oOo---

§ 7.- The Acequia of Belchite (Saragossa)

It starts off the spillway of the great Cuba or Dam of Almonacid, just by the town of the same name, on river Aguas Vivas. It runs along the Malpasillo gorge to the area of Los Chorros before heading towards Belchite, whose extensive olive groves it irrigates. Especially interesting is the section carved into rock in that Malpasillo and the tunnel section through conglomerates.

Of course, the great protagonist is the Roman dam, traditionally called Cuba, the highest (34 m) of all known in the old Empire. It is 100 m long and 7 m wide at the crest, over which runs the road. Its original capacity is estimated in about six million cubic meters. The massive structure contrasts with the modesty of the acequia. It was declared a Bien de Interés Cultural (BIC) in 2001.

The best study, truly comprehensive, of this dam, is indicated in the literature (4). This study points out some hypotheses about the purpose of such a dam, purpose that, however, remains a mystery. See several more hypotheses about its eventual destination in (12).

The Cuba or Dam of Almonacid on River Aguas Vivas (Saragossa)

The dating by the carbon 14 method places the original construction of the dam between the years 67 BC and 84 AD, with various later repairs and reinforcements, someones very important. Its initial typology differs from the other known dams in Hispania, its display describing three curved walls supported in two buttresses, by the means of arches. The photograph highlights a massive old reinforcement.

---oOo---

§ 8.- The Acequias of Sástago and Escatrón (Saragossa)

In both places of Lower Ebro in Aragon (District of Ribera Baja del Ebro) there are very old ditches fed with flows procedent from the Ebro. As in Belchite, also in Sástago exists a remarkable stretch in tunnel.

On the right bank, the old ditch appears nearby Escatrón, where the rock sections are clearly visible near the intersection of the A-224-Escatrón Albalate del Arzobispo, just south of the second place cited.

Old rock-carved acequia near Escatrón

---oOo---

§ 9.- Waterwheels

(Digression alien to the Roman aqueducts)

Waterwheel of the Monastery of Rueda

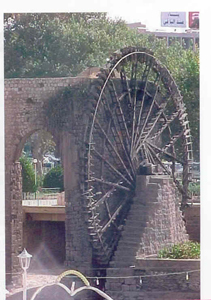

On the left bank, opposite the village of Escatrón, stood the great Cistercian monastery of Rueda, its water supply provided by a self-powered waterwheel. A smaller arm of the Ebro, created in order to power the wheel, started from a great weir. This one crossed and still crosses the river from side to side, forming the acute angle characteristic of this technique repeatedly practiced since very old times in the area of influence of Saragossa. The river arm has been cleaned and the wheel has been recently reconstructed. The medieval monastery was vandalized after the confiscation of its properties in the XIXth c. It stands now beautifully restored, along with the arched aqueduct that connects it with the waterwheel. It operated as a hotel, which closed as a result of the economic crisis starting in 2007-2008.

The waterwheel rebuilt besides the Cistercian monastery of Rueda,

to which it gave its name, according to some, according to others,

the place name would be prior to the construction of the wheel

"Among the provinces of Europe -thus wrote Baltasar Gracián- it is Spain ... " which had, and still has, the largest number of waterwheels.

Fame, as usual, has forgotten the ones existing in Aragon, pondering instead to the highest degree the one called Albolafia, in the Guadalquivir in Córdoba, capital of the Caliphate of the West (See Chapter XII Aqueducts in the Conventvs Ivridicvs XII Cordvbensis, § 4 The waterwheel Albolafia). Moreover, the modern coin of 25 pesetas, with a circular hole in its center, was dedicated to the waterwheel of Alcantarilla, near the city of Murcia, still in service.

The waterwheel of Rueda has been rebuilt with a diameter that I could not find, but in any case exceeding the 15 m that Albolafia was said to have.

Says the ingenious as well as anonymous author of The One and Twenty Books of the Devices and Machines (8) that "water, because of its gravity and weight, cannot by itself go upwards".

The self-propelled waterwheels belie this clearly excessive claim, since they lift water by themselves, using the same force of the flow. That is perhaps why they have always fascinated.

A new one, of the type we might called hamatic, was erected at the Expo Zaragoza 2008 to the delight of visitors. It was built by craftsmen from the city of Hama (Syria), brought for the purpose.

Waterwheel of Expo Zaragoza 2008 built by craftsmen from Hama

The ones of Hama (place name of Hittite origin), on river Orontes (in Arab, nahar al-cAsī), pour only water on one side, while the Aragonese have two wheels attached, with a rosary of pouring buckets to one side and another rosary to the other side. Furthermore, Hama's wheels are wooden ones, and their radii are not real ones, as they actually surpass the center, being tangent to a lesser circle.

A waterwheel in Hama (Syria), on river Orontes

Waterwheels working in parallel in Velilla de Ebro

Hispania's unique case with two parallel wheels. Each wheel is, in turn, double, pouring to both sides. The water lifted to the top is collected in four gutters, two for each wheel, visible in the photo, which converge to feed the irrigation ditches of the Sindicato de Riegos of Velilla, a partner in the restoration.

These wheels were dismantled half a century ago to install a pumping system, the compound consisting of a weir restored upon the great Iberian river, a lateral canal to feed the wheels, a public pool for washing clothes, the two parallel wheels, and a hydraulic mill.

Parallel waterwheels of Velilla; downstream side view

The Colonia Victrix Ivlia Lepida

From the hydraulic complex is visible on the top (not shown in the photograph) the great hermit of Saint Nicholas of Bari, adjoining to the colony founded by the triumvir Marcus Æmilius Lepidus in 44 BC (after the stabbing of Julius Cæsar that year) as Colonia Victrix Ivlia Lepida. First Roman colony in the Provincia Tarraconensis, it was built in what are now the eras of Velilla. It changed its name in Victrix Ivlia Celsa from the year 36, when Lepidus left the triumvirate in his path to exile. The city was excavated partially, accepts visitors, and is equipped with an interesting museum (10).

Velilla's parallel waterwheels; backwater upstream

Hermitage of Saint Nicholas of Bari: main façade

Hermitage of Saint Nicholas of Bari: Romanesque apse

Celsa and KeLZE

Celsa is the Latin version of KeLZE, city by the Ebro, in the region of the Ilergetes, which minted currency of the Celtiberian group of the "three dolphins". A colony Celsa built over a precedent Celtiberian population would explain the name of Belilla (now written Velilla), no doubt alluding to the powerful Celtiberian group of the Belli.

Velilla's bell

This hermitage of St. Nicholas was famous in the XVth and XVIIth Centuries for its bell, known as "campana de Velilla who, it was said, rang "in cross", foreshadowing catastrophes.

So, ringing sine manu and insistently on August 4th, 1435, it suspended the minds of those who heard it. Soon news came that on Friday August 5th, festivity of Our Lady of the Snows, " ... three hours before noon, an arch of the stone bridge being constructed over Ebro in this City [of Saragossa], that was the most noted and sumptuous building of these kingdoms, when about to be finished, suddenly fell, killing five people, and many were wounded".

The superstitious concern rose one grade when, after few days, news came of a major disaster: that this same Friday, at the same hour, after the naval defeat of Ponza, had fallen into the hands of the Duke of Milan the King of Aragon Don Alfonso V the Magnanimous, with his brother Don Juan, King of Navarre - and future King of Aragon - , and a large number of Aragonese, Sicilians and Castilians noblemen (11) and [2].

The ominous predictions became more frequent since then, and over nearly two centuries. Then, the bell fell silent for ever.

(End of digression)

---oOo---

§ 10 and 11. - Rané's Dam and pipelines, and Azubias' Dam (Saragossa)

Rané's Ravine flows into the Jalón to the left by Lumpiaque, a town that some experts identify with the historic Complega of the Celtiberian wars.

The Rané's Ravine, with a significant watershed, has a old dam as well as also ancient (yet undated) ditches slightly upstream its junction with road A-121, between PK 21 and PK 22, about 4 and 1/2 km from the access road to the Sanctuary of the Virgin of Rodanas, among Ricla and Fuendejalón.

In the valley of Las Azubias, east of Rané, and west of road A-1303 between river Jalón and Ainzón, about 5 km south of Pozuelo de Aragón, can be seen the remains of an old dam (still undated), whose type does not differ much from that of Cubalmena.

Old dam in Las Azubias (Saragossa)

The accused Celtiberic imprint of these regions, truffled with ancient caves, is consistent with the interest of the said Celtiberians in irrigation, stated in various parts of Central Aragon.

---oOo---

§ 12. - Aqueduct of Quicena (Huesca)

It runs southwest of the Castle and Abbey of Montearagón, not far from the city of Huesca.

The aqueduct of Quicena in 2009

About this little structure would flow a canal captured from the Flumen, downstream of the current and recent Montearagón Dam, and along the left bank of the river.

The existing ditch is bound to follow a path similar to that of the the Roman canal.

As its direction points towards the city of Huesca, it could have likely served the urban supply of Osca, where we could look for the thermae, everpresent in every Roman city.

---oOo---

§ 13.- Weir of Abrisén or of Fañanás (Huesca)

Abrisén

There is medieval documentation on this deserted village.

On the other hand, the Confederación Hidrográfica del Ebro (CHE) included, already in 2007, in the Hydrological Plan of river Alcanadre (of which Guatizalema is an affluent), a plan for the "Recovery of the medieval village of Abrisén and the Mill of Fañanás".

Weir's location

This interesting weir is on the Guatizalema, about 2 km south of Siétamo. The exit "Siétamo" is the provisional end of speedway A-22. The weir is 1 km south of the way. The city of Huesca is about 9 km to the west and the Huesca-Pirineos airport, at half that distance as the crow flies. Fañanás is 3 km away.

How to reach it

a) From Fañanás, at the south

To reach the weir just drive along a dirt road north from Fañanás (town in the TM of Alcalá del Obispo). In Fañanás, an information panel provides data of the contours, including the weir.

Structures of motorway A-22 over the Guatizalema.

In the background, the svelt bridge linking Siétamo (on the right) with Abrisén's weir (on the left).

The Guatizalema flows from right to left of the photo

a) From Siétamo, at the north

From Siétamo, a dirt road crosses the motorway A-22 on a svelt bridge, and leads directly to the ford of Guatizalema, just downstream of the weir.

Guatizalema's ford in Abrisén: an idyllic landscape

Puppies near the dam: an idyllic landscape

Brief description of the structure

The right abutment, which is the mouth of the acequia (X=725 499, Y=4 665 267, error ±5 m (Datum ED50); X=725 391, Y=4 665 057 (Datum ETRS89), is invisible, hidden as it is by vegetation.

Starting point of the Acequia de Fañanás, on the right abutment of Abrisén's weir

The left abutment is the only visible (X=725 451, Y=4 665 139, error ± 5 m (Datum ED50); X=725 392, Y=4 664 929 Datum ETRS89) - the rest of the structure is hidden under an inextricable tangle -. Can be seen well-shaped blocks, which could be Roman, although smaller than the of dams of Muel or Almonacid de la Cuba.

Weir of Abrisén's left abutment

It is located about 500 meters, and its length, measured from the approximate coordinates ut supra, is 137 m (± 10 m). According to the website which I quote at the end of this paragraph, the maximum height is of 9 m, and its thickness at the crest of 1.7 m, being visible up to seventeen courses of stones. It is a buttress dam. From it starts, on the right bank of the river, the canal currently called Acequia de Fañanás, since it irrigates that municipality.

The medieval documentation calls it Albella's Weir, and in its environs are still remains of a castle and ruins of what could be a Roman villa, abandoned and then reoccupied, like many others, in "the time of the Moors."

Comprehensive information on

www.fanyanas.com/2000/01/el-poblado-y-castillo-de-abrisen.html

Comment

This interesting weir deserves a cleaning of the vegetation that masks it. If also endowed with a picnic area, we would be emulating the Parque del Azud area described in § 18 Aqueduct of Peña Cortada, in Valencia. We would have here the advantage of its proximity to the A-22 (the most difficult and expensive, the bridge over the motorway, is done and operating), as well as the archaeological remains in their environment.

---oOo---

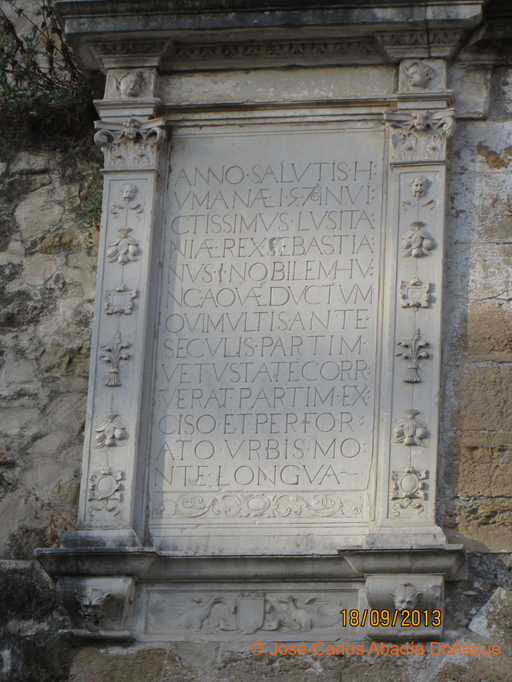

§ 14. - Aqueduct Albarracín-Cella (Teruel)